Vayishlach

(And He Sent)

Echelon

Art Gallery

Oil Paintings,

Prints, Drawings and Water Colors

Vayishlach (And He Sent)

|

©

2009 Drew Kopf |

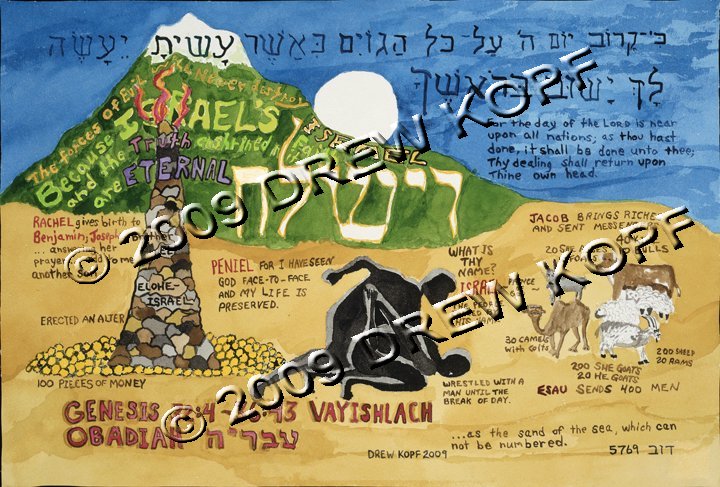

Title: Vayishlach (And He Sent)

Medium: Water Color on Paper

Size: 19-1/2" x 13-1/2"

Available Framed or Unframed

The text afixed to the back of the framed origional and which is provided with each geclee copy, reads as f

Signed: Drew Kopf 2009 (lower center) and, in Hebrew, Dov 5769 (lower right).

Created: December 2008 through January 2009

Original: in the collection of Blake Kraus, Long Island, NY; a gift of the artist on the occasion of Blake's. Bar Mitzvah.

Parshas Vayishlach Vayishlach (And He Sent): |

Anyone who has ever walked alone on a moonlit night along a desolate country road knows how a pervasive darkness like that enables us to some how see things more clearly with just a minimal amount of light. At times like that, we call upon each one of our senses to gather for us what ever evidence they can so that we might learn more about the objects of our attention and concern. Little things become magnified in terms of importance so that we might read the meaning and consequences of those objects even if we can not actually see for certain what they are. The Sedre of Vayishlach (Genesis 32:4 to 36:43) with its companion Haftorah, the Book of Obadiah, tells of the great turning point in our Father Jacob’s life when he returns to the land of his birth from his lengthy and arduous sojourn with Laban, where he had married the love of his life, Rachel, but only after having been duped into first marrying her sister, where he fathered his many sons and where he prospered in spite of the mistreatments he had experienced at the hands of his conniving and deceptive father-in-law. Jacob’s overarching fear was that his twin brother, Esau, still harbored enough resentment and hatred for him that he might wish to take his brother’s life. It had been for that very reason that Jacob had fled from before Esau all those years ago after getting their Father, Isaac, to unknowingly bestow upon Jacob the blessing and birthright of the first born son, which was by rights that of Esau. Jacob could only guess, based on his past knowledge of his brother as he remembered him from all those years ago, how Esau might feel; how Esau might react; and what Esau might do to Jacob when seeing him again face-to-face. To better evaluate his situation, Jacob dispatched, Vayishlach, “and he sent”, messengers, to tell Esau of his pending arrival, but more, to probe what, for him, was a great and terrible darkness, in hopes of learning something that would allow him to know more of what was in his brother Esau’s soul; how Esau felt about Jacob; if Esau hated Jacob; if Esau wanted Jacob to be dead; and, if Esau would, in deed, try to kill Jacob. To mollify the situation, Jacob sent before him a tremendous and surely impressive number of animals as tribute to his brother Esau and as a way to hopefully ease the tensions that he expected their approaching meeting to bring. Jacob also took strategic percussions to insulate himself from his wives and children so that should, in fact, Esau pursue Jacob in a hunt to the death, he would enable his progeny to survive and continue his Father’s and his Grandfather’s mission to bring the world and its peoples the message that the Lord is the One and Only God and that the precepts of how the Lord wishes mankind to live are engendered in the ethical ways as demonstrated and lived out by him and his forefathers. In his isolated position across the river from his divided encampments, Jacob passed through the night alone with his thoughts and his fears, which he faced one-by-one and all at once in what was a grueling and draining struggle to survive and conquer the one person who can do us all in; one’s own self. It comes down to us that he fought with a man; an angel; who finally admits defeat and begs to be released by Jacob and who blesses Jacob by giving him a new name; Israel, by which his descendents would be known from then and onward even until today. He purchases a piece of land and constructs on it an altar called El Elohe-Israel. Pivotal also in this Parsha of Vayishlach is the death of Mother Rachel, who dies while giving birth to Jacob’s last son and her second son, Benjamin, who is the full brother of Joseph, and who will play such an important part in the story of the Jewish people as they move forward into their bondage in Egypt, which prepares them to be free and to appreciate freedom, which is so very important to all that is Holy. The Sedre also makes mention of the death of father Isaac at the age of 180 years and how his two sons, Jacob and Esau, together, and respectfully, bury him. The Haftorah, which is the entire Book of Obadiah, carries the message that the forces of evil will never destroy Israel, because Israel’s faith and the truth enshrined in that faith, is eternal. And, it puts forth the warning: “For the day of the Lord is near upon all nations; as thou hast done, it shall be done unto thee; thy dealing shall return upon thine own head”. The challenge for a painting that would and capture the darkness of great fears, tribulations and unknown feelings while projecting the optimistic message that all would be well with regard to the Covenant that the Lord had established with Abraham our Father came about by using the nature of the watercolors and how they soak into the pulp of the paper giving a myriad of levels of the same color moment-by-moment across the page. When everything is special, it is difficult to make anything special. So, we opted to let the feelings and meanings behind the symbols mix, however they might, as one’s eye drifts from one to another and back again; from the painting as a whole to the elements and phrases within it; and from what one sees with the limited light available; not too differently then when walking along a desolate country road lit only by the light of the moon and calling upon all of our senses to help us understand and know what we may from what is before us. Drew

Kopf © Drew Kopf 2009 |

Price

per Giclee Reproduction on Water resistant Canvas or 310 Gram Hahmemule Art Paper |

||||||

Size |

1 |

2

to 3 |

4

to 7 |

8

or more |

Standard Stretching |

Standard Stretching |

| 5" x 7" | $175.00 |

$150.00 |

$100.00 |

$70.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 8" x 10" | $225.00 |

$170.00 |

$135.00 |

$100.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 11" x 14" | $275.00 |

$225.00 |

$190.00 |

$150.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 12" x 16" | $325.00 |

$275.00 |

$200.00 |

$175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 16" x 20" | $375.00 |

$300.00 |

$225.00 |

$200.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 18" x 24" | $425.00 |

$350.00 |

$275.00 |

$225.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 24" | $475.00 |

$375.00 |

$300.00 |

$250.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 30" | $525.00 |

$400.00 |

$350.00 |

$300.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 30" | $600.00 |

$525.00 |

$475.00 |

$400.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 36" | $725.00 |

$625.00 |

$575.00 |

$500.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 30" x 40" | $850.00 |

$750.00 |

$675.00 |

$600.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 32" x 48" | $900.00 |

$800.00 |

$725.00 |

$625.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 36" x 48" | $975.00 |

$850.00 |

$775.00 |

$675.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 50" | $1,350.00 |

$1,200.00 |

$975.00 |

$875.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 60" | $1,800.00 |

$1,500.00 |

$1.300.00 |

$1,175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| Please Note: | ||||||

| 1. Prices are exclusive of shipping and handling charges, which will be added. | ||||||

| 2. Deliveries to NY, CT or NJ are subject to applicable Sales Tax. Please provide Resale or Tax Exempt Certificate with Purchase Order. | ||||||

| 3. All sales are subject to the conditions delineated in the Terms of Agreement for Sale and Transfer of a Work of Art. Please print and complete a for and submit it with purchase order. Thank you. | ||||||

| 4. Prices are for printing on canvas or on 310g archival art paper. unframed pieces. Please inquire if framing is desired. (646)998-4208 | ||||||

| Abstracts | Drawings | Oils | Still Lifes |

| Architecture | Jewish Subjects | Pastels | Water Colors |

| Books | Landscapes | Portraits | |

| Cityscapes | Nautical | Prints | |

Toll-Free Phone: (800)839-2929

Toll-Free Fax: (888)329-6287

| Echelon Artists | About Echelon Art Gallery | Drawings |

| Oil Paintings | Water Color Paintings | Prints |

| Exhibitions | Art for Art Sake | Helpful Links |

| Interesting Articles | Photographs | Pastel Paintings |

| Artists Agreement | Purchase Art Agreement |

| Geoffrey

Drew Marketing, Inc. |

|||||||

|