Shabbas Zachor

Echelon

Art Gallery

Oil Paintings,

Prints, Drawings and Water Colors

Shabbas Zachor

|

© Drew

Kopf 2012 |

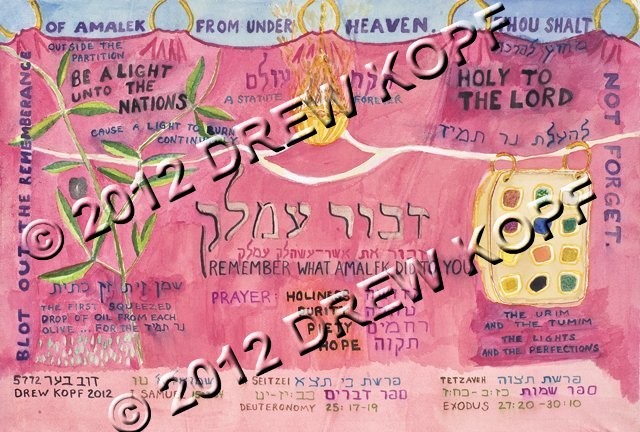

Title: Shabbas Zachor

Medium: Water Color on Paper

Size: 22" x 30"

Available Framed or Unframed

Signed: Drew Kopf 2012 and in Hebrew: Dov Bear 5772 (lower left).

Created: Shevat 5772 corresponding to February 2012

Original: private collection, White Plains, NY; gift of the artist.

The text afixed to the back of the framed origional and which is provided with each geclee copy, reads as follows:

Sedrah: Tetzaveh (Exodus: 27:20 to 30:10) תְּצַוֶּה The 20th Torah Reading in the Annual Cycle of Weekly Torah Readings Mafteer (Additional Torah Reading): Deuteronomy XXV, 17 - 19. Haftarah: I Samuel 15: 2 - 34 |

| Shabbas Zachor: Every Drop Counts |

Tetzaveh: The Mishkan in Detail The Parsha Tetzaveh takes up where the Parsha Terumah leaves off. Parshas Terumah detailed the structure of the Mishkan; the Tent of Meeting; the Holy Tabernacle, which was to be the center of everything for the Jewish People as they wandered through the desert. The Mishkan was where the Lord would dwell among the people. Parshas Tetzaveh details the way things would look and be done within the confines of the Mishkan; what the functionaries would wear; how the holy garments, implements and fixtures would be made; what rituals would be conducted by whom, where, when and in what manner; and, in a way of putting all of this in proper perspective, what the downside costs would be to those who might fail to execute the procedures as prescribed or, whether wittingly or unwittingly; purposely or entirely by accident, in any way demonstrated disrespect for the Mishkan and all it was to represent. Everything about the Mishkan counted. The very first subject of the Sedrah is the degree of purity of the olive oil that was to be used to fuel the lamp that was to be kept burning everyday in front of the Parochess, which was the drapery separating the Holy of Holies from the rest of the world. The oil was not to be just pure; i.e. with any impurities having been filtered out, but, rather, it was only to be made up of the first drop of oil that came from each olive as the olive was gently squeezed until a single drop of oil oozed out from it. The rest of the olive and its oil could be used for other purposes. But, only the purest form of the oil of an olive, the first squeezed drop, was to be used in the lamp outside the Holy of Holies; the Nair Tameed; the Eternal Light. That is exemplary of the level of purity that the Lord was seeking to establish as the standard for the Mishkan and for everything that was done within it. It should be noted that the use of a portable Mishkan was apparently not part of the original plan. It came about when the Exiles from Egypt proved themselves to be unready, if not unworthy, to enter the Promised Land; i.e. for Freedom, and were condemned to wander all but aimlessly through the desert for forty years when, by then, all of the generation who had directly known slavery, would have died. This condemnation had come about due to the actions of the Jewish People during what is referred to as the Chait Ha Meraglim; the Sin of the Spies. The Chait Ha Meraglim was a pivotal time directly following the Exodus when twelve Princes - one from each tribe - were dispatched to scout out the Land of Israel prior to the Jews advancing to capture it from the seven tribes that were then living in it. The scouts, or spies, came back from their mission with two different reports about the land and the prospects of the Jews being able to win against the then current occupants. Two of the spies, Joshua, of the tribe of Ephraim, and Caleb, of the tribe of Judah, described the Land as being everything they were promised it would be and that the people, who stood in their way, could be defeated by the Jews even with little training and no strategic experience. The other ten spies testified that the Land as fine, but to them, the prospects of success in conquering it were dismal. They described the inhabitants as giants who would easily defeat and kill the Jews. The Jews gave credence to the negative report of the ten spies and cried to Moses that he should never have taken them out of Egypt where at least they would have remained alive even if they had been and would have had to have remained slaves. It was clear to G-d that anyone who was ready to go back to being a slave at the first sign of adversity, was not ready to be free. Since they had “cried” as they did, G-d decreed that that day, which was the ninth day of the month of Av, Tisha B’Av, would be a day of tears forever for the Jewish People. The journey to the Promised Land was then rerouted to include what would amount to a forty year detour through the desert. At that point, the need for the Mishkan became clear and the inner workings of the Mishkan needed to be set forth; thus, the precepts and descriptions that make up Parsha Tetzaveh.

Mafteer: Remembering Amalek Shabbas Zachor is the second Sabbath of the four before Passover. We are reminded of our place among the nations; of our own mission in the world; to be a light to the nations of the world. We see that in the very first line of the Sedrah when the olive oil mentioned in it is described and its use as fuel for the lamp that will illuminate the area between the Holiest Place on earth, the Holy of Holies and everything else in the world. The High Priest was to serve as the conduit from and to the Lord for us and, through us, for and to the rest of the world. On Shabbas Zachor, the rabbis have us read a special Mafteer Alleah taken from Deuteronomy 25:17 - 18 to make certain that those who hear it will fulfill the commandment to “remember Amalek” and what he and his kind did to the Jewish People. We then read the Haftarah for Shabbas Zachor, I Samuel 15: 2 - 34, because of the tie to Haman, who was a descendent of Amalek and because Purim is just ahead in the coming week. The Mafteer reading reminds us that as perfect as the world is, there is work yet to be done by us to bring it to its ultimate level of perfection. That is the role of the Jewish People; Teekun Olum, repairing the world. But, when we think about it, it would have been easy for the Lord to wipe out Amalek. Why would he need the Jewish People to do it for him? There were other instances when the Lord deemed it necessary to “get rid of” people who needed to be gotten rid of. According to legend, the Lord had made other worlds before this one, which had not worked out as well and which he destroyed. It is fair to assume that there were “people” in those worlds who did not match up to His hopes for them. Within our world, there are things that needed and still need to be perfected; mostly dealing with us, mankind and our own imperfections. One example of such an imperfection was seen when Noah was called upon to help give the world, or mankind at least, a new start because there had developed in man a propensity towards a way of life that was not in G-d’s plans as right for us. The Lord brought the flood and wiped out those who had demonstrated definitively that they could never measure up to the expectations of the Lord and His basic requirements for the world; from whence came the “Shevah Mitzvos Shel B’Nai Noach” or the Seven Noahide Laws that serve to this day to differentiate civilized man from barbarians. The next refinement in the development of G-d’s plan for the world and for us was the advent of Abraham and his descendants who gave the world the three major religions but within whom dwells a certain amount of animus, some of which is represented in Amalek, who, like those exterminated during the flood, were felt by G-d to be unfit and unworthy of this world of His; of ours, to where He ordered them to be destroyed. But, again, the same question as before: Why did He, the Lord, not wipe out Amalek as He did those who were wiped out by the flood? Why did He leave this task to us? Of course, if we look back at the flood, Noah may not have raised a hand or taken up a weapon against anyone, but his participation was none the less, of that of an active participant. He was under orders and he was foursquare behind the will of his creator.

Haftarah: King Saul and his Mission against Amalek Shabbas Zachor takes its name from G-d’s commandment to the Jewish People to “Remember what Amalek did to you” (Deuteronomy XXV, 17), which we shorten to “Remember Amalek.” Esau, who bitterly resented his twin brother, our forefather, Jacob, was the grandfather of the first Amalek, who carried on his grandfather’s “tradition” of hatred toward the Jewish People by attacking the Jews of the Exodus while they were en route from Egypt to the Promised Land; the Land of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; the Land of Israel. War is war. When the prospect of taking over a land that had been your family’s but from which your family had been displaced for some four hundred years and which now was being returned to it by the Creator Himself, it would be very much expected that your efforts to repossess that land would be vigorously and vehemently opposed by the current inhabitants. But the Tribe of Amalek was not one of the seven tribes dwelling in the Land of Israel when the Jews were returning to repossess it after their long exile in Egypt. Amalek lived outside the Land of Israel; to the North, and, therefore, had no reason to make any kind of attack against the Jews; neither in retaliation for an attack against them nor preemptively since there was nothing that the Jews were doing that could have been interpreted as threatening to Amalek. So, when Amalek swooped down and attacked the returning exiles, it was a complete surprise and one which those serving in defensive positions along the route of the march toward the Promised Land could never have imagined taking place. After all, even in those early times, there existed a certain code of decency, an unwritten “Geneva Convention-like” way of doing battle that precluded combatants from warring in certain ways. Attacking an enemy, even in an ambush type of assault, was fine. But, to attack one’s foe where there was not even the slightest chance of resistance or retaliation; to attack the old, the sick and the infirm, those who were clearly unable to defend themselves in any way and, who therefore, would be and had been left unguarded at the end of the line of march because no self-respecting enemy would even consider directing any kind of lethal actions against them, was absolutely unheard of; impossible; unbelievable; inhuman; amazing and, therefore, unforgivable, and, now and forever, commanded by G-d, not to be forgotten; i.e. to be remembered forever. Remember Amalek. What was it that was so hateful about the Jews to Amalek? Amalek did not believe in G-d. The Jews, who did, were an anathema to Amalek. It was the hatred of the Jewish People by Amalek combined with Amalek’s total disrespect for G-d, as demonstrated by Amalek’s complete fearlessness of the Lord in acting with utter disregard to G-d, who sees and knows all, by attacking the weak and defenseless just because they were Jews, which demonstrated the complete lack of worthiness of those who carry the heritage of Amalek within them and which earned for the tribe of Amalek and their descendants forever the decree against them as commanded to King Saul by the Lord through the Prophet Samuel: to mobilize the nation and to eradicate all that is or is in any way connected to Amalek; every living thing is to be killed. The lines “So let it be written. So let it be done.” from the 1956 film The Ten Commandments by Cecil B. DeMille come to mind. They were spoken by Yul Brynner in the role of Pharaoh Ramses II when he made a decree. One would think that when the Lord’s decree against Amalek was delivered to King Saul, King Saul would have followed it to the letter. One might think that, but the way Saul actually either interpreted the decree or chose to comply with it was far from “So let it be written. So let it be done.” It was not even close. The way Saul went about executing G-d’s judgment against Amalek recalls the way Eve got herself and Adam into trouble regarding the Lord’s commandment to them regarding not eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Eve in her enthusiasm perhaps, tells the Snake, who was Satan in the guise of a snake, a slightly different version of what the Lord had actually commanded them. She misquoted the Lord by including in her reiteration of G-d’s warning the word “touch”; i.e. that they were not even allowed to touch the Tree. “You shall neither eat of it nor touch it, lest you die.” (Deuteronomy 3:2). Touching, of course, was never part of the decree. It was only forbidden for them to eat from the Tree. Nothing about touching had been mentioned. But, once Eve accepted that it was part of the decree, and once she could see that touching the Tree brought about no negative reactions, she reasoned, with the “help” of the Snake, that eating from the fruit of the Tree would be similarly uneventful. So, she ate the fruit of the forbidden Tree and gave the fruit to Adam to eat as well. How often do we fool ourselves into believing that something we know darn well is bad for us will do us no harm if we just do a tiny bit of it? Eve actually believed that what was not said had been said; that G-d actually told them not to “touch” the Tree even though He had only forbidden them to “eat” from the Tree. Soon after, when G-d challenged Adam about eating from the Tree, Adam pointed his finger at Eve as having caused him to do so. But let’s be fair. Was it really Eve who went off the deep end in this instance? Was Adam really the victim of Eve’s exuberance or, perhaps, was it Adam himself who had shot himself in his proverbial foot and brought down his helpmate by having done so? After all, Eve had not yet been created when the Lord gave Adam the rule concerning the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil; i.e. “… for on the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.” (Deuteronomy 2:16). How would Eve have even known of the “rule?” Did the Lord hold a special introductory course; Garden of Eden 101, for Eve so she could be brought up to speed on what life in the Garden of Eden was all about? Probably not; or we would have been told about it in the Torah. Eve must have learned about the Tree and the “rule” concerning it from Adam. It is quite possible therefore, and perhaps even highly likely, that it was Adam, in his effort to stress the importance of the “rule” about not eating from the Tree, that he himself had added the part about “not even touching it” to his account of what G-d had said and thereby sowed the seeds of his own downfall. In a similar way, it appears that King Saul first made a quasi-amendment to the dictum to annihilate Amalek by warning the Kemites, a tribe of people who lived near by, to leave the area and save themselves before he launches his attack against the Amalekites. If he had included the Kemites along with the Amalekites, he would not have been far from wrong since the two tribes were apparently not just in close proximity but may have related with each other more intimately than that. But, apparently, his sticking to the strict interpretation of the Lord’s decree regarding the Amalekites, i.e. saving the Kemites, was appropriate since they were not in fact Amalekites. But, it is almost as if having saved the Kemites made it easier for King Saul to then lean away from what should have been his prime directive; to “kill the Amalekites and all living things connected to them.” (Samuel, 15:2) The order to King Saul from On High was to kill not to capture. So, the very first bit of news regarding the success of King Saul’s assault on the Amalekites has got to be a bit of a shock to even the most casual follower of Biblical stories: “He captured Agag the king of Amalek alive and all the people he put to the sword.” (Samuel 15:7). Captured alive? Why alive? All of the Amalekites were supposed to have been killed. Why was Agag, the King of the Amalekites saved alive? This is where the story gets a little hard to understand; odd. We are told that “Saul and the people took pity on Agag and on the best of the sheep and the cattle, the fatted bulls and the fatted sheep and on all that was good; and they did not destroy them; only what was despicable deteriorated did they destroy.” (Samuel 15:9). What is going on here? Since when does a King get soft like that and save a man alive who was ordered to have been killed? And, since when do the people have any say in showing pity on anyone when they have been directed to kill everyone; take no prisoners? What happened here? And, while we are at it, why would they save the better of the animals while slaughtering the less desirable ones when they were commanded to slaughter them all? From where did that interpretation of their mission emanate and how did it get adopted as the right thing to do? We can speculate about Agag, who may have had a magnetic personality or who some how was able to appeal to the “humanity” of his enemy and gotten King Saul himself, as well as his subjects, to ignore the commandment of the Lord and, instead, to get them to think that they were doing the right thing by preserving Agag and planning to use the captured livestock for fabulous sacrificing ceremonies to the Lord. But, what really happened? Were the people really complicit in the failure to follow the Lord’s commandment to King Saul? Or, is this not a similar situation to the one regarding the eating of the fruit of the Tree of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden? Did Saul somehow convince himself that the honorable or gentlemanly thing for one King to do with another would be to save the other King, Agag, and implicate his own subjects in the self-deception so that should he, Saul, ever be in a similar situation, that he might be saved alive as well? It could not have just come from nowhere. Something had to have brought about this direct disobeying of order. But what was it? We are talking about orders from the Lord G-d being countermanded by an anointed regent and then either “rubber stamped” by his people, or visa versa. What kind of rebellion is that? When Samuel queries Saul about how he carried out his orders, he does so in what might be called a “diplomatic” way. He does not condemn or accuse Saul but rather, mentions the obvious discrepancies and learns from Saul that he seems to have followed the will of the people, or so he says, that they, the people took pity on the best of the flocks and kept them for sacrifices. He says he was afraid of the people and followed their lead. He begs forgiveness. He seems to make a distinction between Agag and Amalek and sees his saving Agag as not being inconsistent with his mission to kill all connected with Amalek. What really happened to bring about this fiasco is left for us to speculate. But, Samuel seems to know or understand what transpired and does not take any action against King Saul. He has Agag brought to him and he finishes the job that Saul had failed to do. With Agag finally killed and King Saul back on track, there was a formal apology where Saul prostrated himself before HaShem and in front of the elders of Israel that helped straighten things out, Samuel goes his way and Saul goes his and all seems to be forgiven, but certainly not forgotten. The sages say that during the time that Agag was temporarily spared, his wife conceived and somehow escaped, perhaps among the Kemites, to continue the line of Amalek, which eventually some 500 plus years later led to the near destruction of the Jewish People by Haman of the Purim story (who is said to have been a descendant of Amalek).

What is the take away? If that is really all there is to this episode, then the whole thing ends up being fairly innocuous. There were some pretty evil and inhumane people out there, who were sworn to and did kill Jews. Those charged with destroying those dangerous and anti-G-d aberrations failed in their mission, though they did so not for lack of skill or ability, but out of some kind of misguided values that they allowed to color their actions, which allowed those evil doers to live on and to continue attacking and threatening the security of the Jews even until today. We can leave these stories right here on the page to read and remember from time-to-time. Or, is there something we can take away from this continuum of evildoers escaping their end only to arise again-and-again to threaten the very existence of the Jews, G-d’s chosen people, even in the face of the Lord’s continued support and shepherding? Is there nothing we can learn from all of this that can effect how we act today? What is the lesson that we should be learning from this special Shabbas Zachor? Are we just supposed to “remember Amalek” or is there something more to the commandment? One thing we learn from the story, is that It is important to follow the Lord’s commandments because it may be long periods of time before G-d’s plan becomes fully realized and even the smallest deviation from His commandments may, way down the road, have drastic and even disastrous effects such as was almost the case in the Purim story, when a descendant of Agag, who was a descendant of Amalek, became perfectly positioned to annihilate the entirety of the Jewish People. Perhaps that is our take away message: that everything counts. We need to live as if each of us is like King Saul; a person with a chance to affect the future in the exact same way. So, there is nothing in any of our lives that does not count. It is all important; every bit of everything that each of us does counts; and counts big. As we learn at the very beginning of the Sedrah, only the first drop of oil squeezed from olives was to be used for the light that would burn in front of the Holy of Holies. What is the difference between the first drop and any drops thereafter? What would the difference be if any but the first drop of oil from an olive be included among all the other drops of oil? What would be the harm? The truth is, we really do not know. But, whatever the difference or the harm might be, it must be significant or it would not have been required to be done in that way. Or, even if such attention to detail was being asked of the Priests to demonstrate the importance at the microcosmic level so that they would bring that approach to everything that they would do in the Mishkan on the macrocosmic level; it certainly gets the point across; that everything counts. The rabbis point out a relationship between the “purity” of the olive oil for fueling the light of the lamp that is to shine in front of the Holy of Holies through out the darkness of the night and the level of purity desired for those who were to be performing the duties connected with the Mishkan. Maybe that is our lesson, our take away message from the Sedrah, the special Maftir and the Haftarah for Shabbas Zachar: If it is from the Lord, it is not for us to second guess His reasoning; but to follow His lead; to do what we are asked to do and to trust that it is right for us and for the world. Is there some basic flaw in mankind that started with Adam and Eve, which causes us to do such things as this; to overstate like Adam did to Eve; to be so vile as those killed in the flood; to attack defenseless old and helpless people like Amalek; or to take a less than strict approach to the carrying out the Lord’s commandment in the way that King Saul did in his approach to destroying Amalek? Is it that on a situation-by-situation basis, where we are faced with making command decisions, that we some how opt to do things that may, and in these instances did, result in failure? Adam and Eve got ejected from Eden. The generation of Noah was drowned in the flood; Amalek got condemned for his dastardly ways. Saul had certainly been aware of Amalek. Knowing what he knew, how could King Saul have been so “afraid” of his people and allow them to permit Agag to be saved and for the flocks and animals to be retained rather having all of them put to the sword immediately as ordered by the Lord? What seems apparent is that we, mankind, are in our very make up, prone to make mistakes, to misinterpret, to misconstrue, to embellish and fabricate even in an effort to protect ourselves against doing what we are loath to do, but, given our very nature, may do any way. The rules that G-d has laid out for us were necessary for Him to have stated as such because we surely would not have developed them on our own; it is simply not in our nature to have done so. We needed those rules because without them we might tend towards our baser nature; to the nature that dominates in Amalek. It is possible that whatever makes Amalek do as he does could be; is, in us as well and could be waiting to trip us up into becoming as evil as Amalek could ever be. None of us wants to say it, but Amalek is related to us Is that why G-d does not wipe out Amalek but, rather, called on us to do so? Is the, or at least part of the Tekun Olum, the repairing of the world mission of the Jewish People some how connected to dealing with the Amalek tendencies that might still be lingering inside of us and that need to be purged or stilled in someway. If that is the case, then why would we need a commandment to “Remember Amalek” when all we would need to do each day is to look in the mirror? Why? Perhaps it is because part of our nature is to sublimate or accept our weak points. We are not going to admit, least of all to ourselves, that we could ever be as monstrous as Amalek. If he ate from the Tree, Adam was to “surely die” but he did eat from the Tree and he was not immediately killed. He was ejected from Eden. King Saul failed to follow the orders as dictated by Samuel but King Saul apologized and was apparently forgiven. Unlike those killed during the flood and unlike Amalek; Adam and Saul were apparently not evil to the core, they were G-d fearing, respectful but somewhat lacking in exactness. Can we be as pure as the first drop of oil gently squeezed from an olive? No, we can not. But, we can try to be. And, if we should slip in our efforts to be pure, we can ask to be forgiven and try again. The understandings that we can err and seek forgiveness is a key component to sublimating, if we can not actually drive out, eradicate or annihilate what ever it is that is or might be within us that harkens back to Amalek. Forgiveness was not in the vocabulary of Amalek. But, it can and must be in ours if we are to survive and thrive. We can be as pure as we can be in all that we do with what life provides to us. In doing so, we can be ready, like the first pure drop of oil gently squeezed from an olive, to use the energy that is within us to help illuminate the world so that everyone including ourselves can see that life is for doing good for ourselves and for others without hurting anyone and for doing so until the last drop of the strength we have is completely and brilliantly consumed. Drew

Kopf © Drew Kopf 2012 |

Price

per Giclee Reproduction on Water resistant Canvas or 310 Gram Hahmemule Art Paper |

||||||

Size |

1 |

2

to 3 |

4

to 7 |

8

or more |

Standard Stretching |

Standard Stretching |

| 5" x 7" | $175.00 |

$150.00 |

$100.00 |

$70.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 8" x 10" | $225.00 |

$170.00 |

$135.00 |

$100.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 11" x 14" | $275.00 |

$225.00 |

$190.00 |

$150.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 12" x 16" | $325.00 |

$275.00 |

$200.00 |

$175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 16" x 20" | $375.00 |

$300.00 |

$225.00 |

$200.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 18" x 24" | $425.00 |

$350.00 |

$275.00 |

$225.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 24" | $475.00 |

$375.00 |

$300.00 |

$250.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 30" | $525.00 |

$400.00 |

$350.00 |

$300.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 30" | $600.00 |

$525.00 |

$475.00 |

$400.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 36" | $725.00 |

$625.00 |

$575.00 |

$500.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 30" x 40" | $850.00 |

$750.00 |

$675.00 |

$600.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 32" x 48" | $900.00 |

$800.00 |

$725.00 |

$625.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 36" x 48" | $975.00 |

$850.00 |

$775.00 |

$675.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 50" | $1,350.00 |

$1,200.00 |

$975.00 |

$875.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 60" | $1,800.00 |

$1,500.00 |

$1.300.00 |

$1,175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| Please Note: | ||||||

| 1. Prices are exclusive of shipping and handling charges, which will be added. | ||||||

| 2. Deliveries to NY, CT or NJ are subject to applicable Sales Tax. Please provide Resale or Tax Exempt Certificate with Purchase Order. | ||||||

| 3. All sales are subject to the conditions delineated in the Terms of Agreement for Sale and Transfer of a Work of Art. Please print and complete a for and submit it with purchase order. Thank you. | ||||||

| 4. Prices are for printing on canvas or on 310g archival art paper. unframed pieces. Please inquire if framing is desired. (646)998-4208 | ||||||

| Abstracts | Drawings | Oils | Still Lifes |

| Architecture | Jewish Subjects | Pastels | Water Colors |

| Books | Landscapes | Portraits | |

| Cityscapes | Nautical | Prints | |

Toll-Free Phone: (800)839-2929

Toll-Free Fax: (888)329-6287

| Echelon Artists | About Echelon Art Gallery | Drawings |

| Oil Paintings | Water Color Paintings | Prints |

| Exhibitions | Art for Art Sake | Helpful Links |

| Interesting Articles | Photographs | Pastel Paintings |

| Artists Agreement | Purchase Art Agreement |

| Geoffrey

Drew Marketing, Inc. |

|||||||

|