Shabbas Parah

Echelon

Art Gallery

Oil Paintings,

Prints, Drawings and Water Colors

Shabbas Parah

|

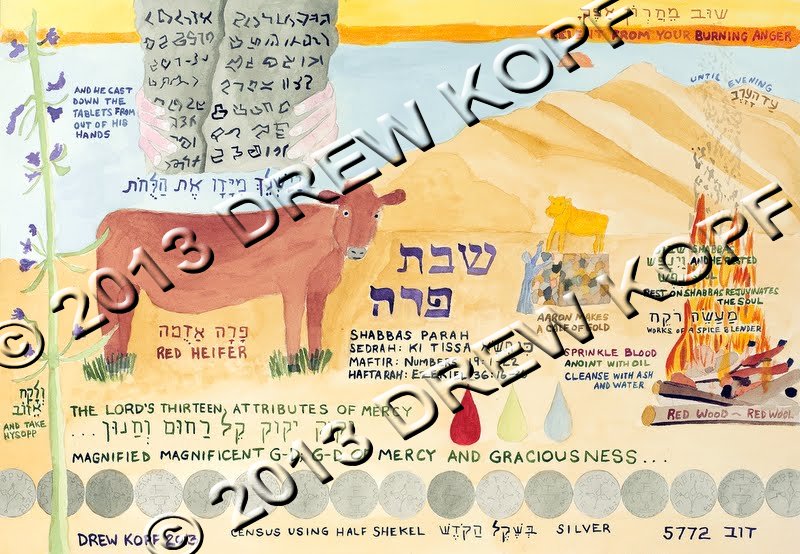

Title: Shabbas Parah

Medium: Watercolor and Graphite on Paper

Size: 20" x 28" nominal

Available Framed or Unframed

Signed: DREW KOPF 2013 Lower Left and 5772 Dov (in Hebrew) Lower Right

Created: February 2013

Original: Sigmund A. Rolat of New York, NY; a gift of The Jewish Post of New York and the artist.

The text afixed to the back of the framed origional and which is provided with each geclee copy, reads as follows:

Sedrah Ki Thissa The 21st Torah Reading in the Annual Cycle of Weekly Torah Readings Exodus 30:2 - 34:25 |

Shabbas Parah: Everything and Everyone Counts by Drew Kopf February 12, 2013 © Drew Kopf 2013 |

The Torah relates the story of the Jewish People as they advanced from their long history of slavery in Egypt to Geula, Redemption. What they went through during the Exodus and in the period directly thereafter stands as the backdrop for Shabbas Parah. The stresses our ancestors experienced along the way were completely new to them. The decisions they made as each event evolved were motivated strictly based on what they knew as fact and how secure they felt at each moment. If we hope to benefit in some way from their amazing experiences, we would do well to understand as much about them and the times in which they lived as possible. On Shabbas Parah, as we read Parshas Ki Thissa, it is almost Passover. A special Maftir (the final section of the Torah reading service on a Sabbath or a holiday) and a special Haftarah (a reading from the Prophets or the Writings that echoes some part or message of the Torah portion being read on a Shabbas or holiday) are substituted for the ones usually read with this Sedrah. Preceding Passover, proper steps to become ritually clean were to be taken as preparation for the eating of the Pascal lamb, which is why the law concerning the ashes of the Parah Aduma, the Red Heifer, is read as the Maftir Alliah: Numbers 19: 1 to 22, during the Torah Reading Service on Shabbas Parah. [Alliah: literally, going up; because one is being called up to read from the Torah]. The special Haftarah, taken from the Book of Ezekiel 36: 16 to 36 (38) deals with moral purification, something that the Jewish People had allowed to fall by the wayside in the years before the destruction of the Holy Temple in 586 BCE, which was during the lifetime of the Prophet Ezekiel ben Buzi (623 BCE – circa 575 BCE), who was a Kohain, a Priest of the Holy Temple, living in exile in Babylon. Parshas Ki Thissa famously tells the story of the Sin of the Golden Calf, Moses angrily throwing down the two tablets of stone with the Ten Commandments that had been engraved by the Lord Himself and of Moses climbing back up the mountain with the second set of tablets to be engraved and pleading to G-d to forgive the Jewish People and to allow them to continue to be His People and He their G-d in a covenantal relationship originally made with their forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob where they, the Jewish People, would serve as a Light to the Nations of the World by leading, through their example, to live in Peace. When we read about such powerful moments as the Sin of the Golden Calf, there may be a tendency to pay attention to the headlines, so to speak, but to let the details and the less stunning events stay on the page; all but ignored. We do so at our peril as we may well be missing key learning moments that the Torah is placing before us. We would then live out our lives without the boost we might have gotten from having gained an appreciation of where we, today, fit in to what may seem like mere tales of yesteryear but which can also be seen as a kind of runway leading up to the lives we live today. It would be a shame indeed if we came this far and got this close to the message that may be waiting there for us to learn how better; or perhaps how best, to live our lives for our own self-betterment and for the betterment of us all, and then to continue on unaware of what we had missed. The Sedrah Ki Thissa, Exodus 30:11 – 34:35, first tells of the taking of a census using a Half Sheckel of silver donated by each man of fighting age, twenty years old and older, as the “counting device” and the Half Sheckel is defined as not the common “trade” Sheckel but the Sheckel connected with the Sanctuary, and that these contributions are to be considered as a kind of ransom for their souls so that they not be subjected to death by plague, which happened elsewhere when a census had been taken by simply “counting heads.” The collected silver is to be used in the construction of the Mishkan; the Tent of Meeting, as a memorial for those souls. The Torah then tells us that Moses is to make a laver or wash basin of brass to be placed between the Tent of Meeting and the Alter for the Kohanim (Priests) to wash their hands and feet and that this was to be a custom for them to follow forever so that they will not die. Then, we learn that certain spices in significant enumerated quantities were to be prepared by a person with unique expertise in that type of thing who would mix the spices and make a kind of ointment or salve which was to be used to anoint or to smooth on to or to coat the various parts of the entire Mishkan and many of the elements it housed. Still other spices were to be prepared by a similarly talented spice expert in a dry mixture, similar to what we term today as a potpourri, to be located where the important work of the Mishkan was to be done. We are told again the exact spices and their respective quantities and that it would include one particular spice, Chelbanah; Galbana, that is foul smelling, but which is to be included in the mixture none the less. No. This is certainly not as exciting and as memorable as the incident of the Golden Calf or of Moses smashing the Tablets of the Ten Commandments. But, there are some observations to be made from all the details presented to us: Number One: Everything and everyone counts. The Silver Half Sheckels redeemed not only the souls of the men of fighting age but of all the people. We learn later that the silver collected was to be made into the joining elements that would allow the Mishkan to stand on its own and to remain intact. Number Two: When it comes to something holy, such as the Mishkan, the best quality silver and the largest measure of it is to be used as the standard for contributions and not a lower echelon option. Number Three: The Mishkan is to be the center of everything in the camp in every possible way. So, the aromatic coating of the spice ointment that will anoint almost every part of the Mishkan would send its distinctive aroma wafting through the camp and touch the many members of each of the tribes with no measurable regularity or predictability but just based on how close one might be to the Mishkan, how sensitive one’s sense of smell might be and how soft or hard the breeze in the wilderness might be blowing on any particular day or evening. And, that aroma, which would unmistakably mean the Mishakan because it is forbidden to be replicated or used in any way by any one for any purpose, would serve as a keen reminder that the Lord was in their midst. [We could really use something like that today. All we might need to help us stay well oriented is a trace of a special scent in the air that would remind us that the life we are leading is not a practice session for something else to come but the real thing, right now, and that as we live our life, the Lord is similarly in our midst]. Number Four: Those participating in the work of the Mishkan, the Kohanim, were to be ready and focused in everyway as symbolized by the washing of their hands and feet before beginning their work or that they would be putting their very lives at risk for not having done so. Number Five: The Mishkan is to be in the middle of the entire community and be there for the benefit of all. This is symbolized by the inclusion of Galbana, the foul smelling spice in the dry spice concoction kept at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting. The Galbana can be seen according to Rashi, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki (1040 –1104), to represent those people who have sinned in some way but who are still to be considered as part of the community. That is, or, at least should be seen to be as true today as it was at the time of the Mishkan. If we are honest with ourselves, we will admit that we tend to keep pretty strict lines of demarcation between us and those who we regard as “unworthy” or perhaps “less worthy” might be more accurate. The ironic truth is that others are probably doing the very same thing to put us on the outside their own worthiness borders. Perhaps a special scent floating through the air that includes some unsavory smells in it to remind us that we are all in this together would be a good thing for us to have around today as well. Then, with no fanfare, we are told the story of the Golden Calf, which hardly needs repeating except for the question that remains unanswered after it is completely spun out: What motivated those among the Jewish People waiting for Moses to return from his forty days and forty nights on the mountain to approach Aaron as they did to make a god for them? There is a discussion among the Miforsheem, the Biblical commentators, about Moses having been late in his return from his meeting with G-d on the mountain. Supposedly, he was due back in forty days but how the days were counted or when the count had begun and when he was actually due back, was unclear and those who were more “impatient” apparently got frightened and turned to Aaron, who had been the voice of Moses to the Jewish People, for something to pacify their anxiety. But, the Sin of the Golden Calf can also be seen as part of what was a protracted process of filtering out of those who were not truly committed to the G-d of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and those who truly thought they were but were not, or who wanted to be but who were not, or those who were perhaps trying to believe; to have faith, but who, even with the miracles of the Ten Plagues so recently experienced by them, could not accept G-d as G-d Almighty, King of Kings, and stay the course until Moses returned. No. They needed a god, small “g”, to tide them over. And that was unacceptable to G-d, big “G”, and was of such an offence to Him as to be punishable by death. We are told in the Sedrah that Moses orders the Kohanim who follow G-d, to put three thousand men who had worshiped at the feet of the Golden Calf to the sword. The other idol worshipers were killed by a plague. These were not the first such Jewish non-believers who died for similar reasons as part of the transition from slavery in Egypt to Freedom in the Promised Land. Many died during the night of the Passover when the Angel of Death killed the first born sons of all in Egypt except for those Jews who had followed the Lord’s directive and slaughtered a lamb and painted their doorposts with the blood of the lamb as a sign of their belief in the Lord. Jews knew that the Egyptians worshiped animals so for a Jew to slay a lamb and paint his doorposts with its blood would have been a very brave thing to have done in front of the Egyptians unless his belief in G-d was very strong. For those for whom it was beyond their belief and who therefore failed to kill a lamb or chose not to paint its blood on their doorposts, not doing so became a kind of litmus test that they had failed and for which they were removed from the numbers of the Children of Israel by being killed by the Angel of Death on that woeful and yet wonderful night. Thus, the shaping of the Jewish People who came out of Egypt was not what could be called a straight line curve by any means. And, it really could have been worse than that. In the next portion of the Sedrah, Moses learns from G-d directly of the events of the Golden Calf. He then climbs down the mountain and all the while must have been stewing in his own anger and disappointment at his followers and at how fickle they proved themselves to be. Upon seeing the Golden Calf, Moses threw the Tablets with the Ten Commandments down with such force as to break them into unreadable shards. He then pulverized the Golden Calf, mixed the dust into water and had the participants drink the brew. It is not clear what, if anything, drinking that mixture did to them but, no matter, because they too would eventually be “edited out” of the congregation for also having been unready for Freedom and for the way of life that G-d had planned for them; a way of life that was pinned on believing in the Lord and following His commandments. Actually, the path to redemption for the Jewish People deviated almost completely when Moses was still on the top of the mountain just at the point when G-d told him about the Sin of the Golden Calf. G-d also told Moses that He was through with this group, the Jewish People he had been leading, and that He, the Lord, planned instead to start all over again with Moses as the new progenitor. But, Moses argued against that plan and in favor G-d’s original pact that had been made with the Patriarchs. G-d agreed and Moses climbed down the mountain to lead his people forward to Canaan. There may seem to be a bit of an inconsistency here that deserves some attention. Why would G-d have negated the readiness of those left after so many had in essence removed themselves from the Jewish Community by demonstrating their lack of belief in the Lord, and, thereby, leaving those who were apparently true believers and, therefore, it would seem, ready for Freedom and ready to follow G-d on the path to Geula; Redemption? Was G-d just testing Moses by telling him of the plan to start afresh with him and to effectively abandon the remaining Jews? Or, were those who did not participate in the Sin of the Golden Calf somehow tainted by having been so close to the deed and by having allowed it to take place at all instead of trying to have stopped it? Edmund Burke said, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” Moses argued not so much for them, but for G-d’s original plan, so the fact that they were spared and permitted to continue on the journey to the Promised Land does not really mean that they were totally forgiven for what they did not do; just not punished for it. Of course, we learn later with the Chait HaMiragglim; the Sin of the Spies, that they too would not be judged to be ready for complete redemption, for they would be the ones who would cry to Moses for having taken them out of Egypt only to die at the hands of the Canaanites. Their punishment for that effrontery though was not death, but rather, to wander through the wilderness for forty years until their entire generation, the last generation that knew first hand the feel of the lash of slavery was dead. So, in a sense, to have started all over from scratch with Moses may have been a plan to follow and not just a test of Moses. (But, what then would have been the purpose and value of the time and tremendous travail suffered by the Jewish People during their 400 years of slavery in Egypt?) There was actually a foreshadowing of G-d’s leaning away from, if not fully rejecting that particular representation of the Jewish People. It comes when G-d informs Moses that an Angel will go before them in the form of a cloud and that G-d’s Shechenah, His Spirit, which was to have resided in the area of the Mishkan referred to as The Holy of Holies, will no longer be in their midst. One might ask, what then is the need to have a Mishkan if its main purpose, to house the Shechenah, is no more? But, the other work of the Kohanem would need to continue and the place for the Ten Commandments would be in the Mishkan as well. Though not discussed in this Sedrah, it is interesting to note that not only were the second set of stone tablets that Moses engraved with the Ten Commandments placed in the Mishkan but so too were the shards of the broken tablets. This can open all sorts of thinking as to how good and bad, achievements and mistakes, which are all part of life and need to be included in our understanding and appreciation of everything we do and everyone who is doing it. As we noted with regard to the building of and serving in the Mishkan, everything and everyone counts. Moses is told to bring two new stone tablets up the mountain so G-d could engrave the same words He had on the first tablets, which he did. At that point the Lord stated what are known as the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy, which are: “The Lord! The Lord! A God compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; yet He does not remit all punishment, but visits the iniquity of parents upon children and children’s children, upon the third and fourth generations.” This has become the key prayer used when repenting and asking for forgiveness in the various communal prayer services through the year. “AdoShem. AdoShem. Kail Rachoom ve Chanoon…” as on Yom Kippur. [The translation that is almost always given for this phrase where G-d’s name is repeated is “The Lord! The Lord!” as offered above. But, Hebrew is different than English when words are repeated in this manor. Simply translating them as two separate and unrelated instances of the same word may well be leaving out the intention of the author. Doubling a word in Hebrew indicates multiplying the meaning of the word exponentially. We might want to translate the phrase containing G-d’s name twice in a row in a way that brings across the meaning of repeated words in Hebrew: “Magnified magnificent G-d” and not merely as “G-d G-d or “Lord Lord” or even as “The Lord! The Lord!” with exclamation points to help out. There are no exclamation points in Hebrew. Translators who use them are trying to convey the emphasis but for us it needs more. We therefore represent this in our painting in what we refer to as an illuminated way in order to bring the power of the message to a fuller appreciation]. The Torah then recaps the annual cycle of holidays to be observed and outlines in detail what the plan is for removing the tribes or nations that currently inhabit Canaan. Moses is then told to record in writing all these transactions. Moses descends the mountain and his face is radiant such that from then on when he is with people he keeps a mask or a veil covering his face. Moses’ meeting with G-d almost face-to-face was transformative for Moses. He could not know it. But, as the Sedrah ends, we can see the tremendous difference between having come so close to the Lord to where ones face is beaming and how depressed and vulnerable the rest of the Jewish People must have felt knowing that the Spirit of the Lord – The Shecheena – which had been expected to have been in their midst, in the Mishkan, would now be reserved and away from them. There is a disparity gap here perhaps that also bares investigation. Moses the man raised in the court of the Pharaoh as an Egyptian prince and who was “Kefad Peh”; heavy of mouth or who spoke with great difficulty, most probably because he either spoke no Hebrew at all, (after all why would an Egyptian prince have been encouraged or taught to speak the language of the slaves?) or, if he did speak Hebrew, it must have been with a very heavy Egyptian accent that his brother Aaron had to serve as his interpreter and veritable voice to the Jewish People, gets to be as close to the Lord as anyone except for perhaps Adam Ha Reshone, the first man, and Avraham Avenu, Abraham our Father, have ever been. And, then, on the other end of the spectrum, there are the rest of Jewish People of that generation with a 400 year background of complete and utter slavery, where time was never their own in any way, with only the vaguest of ancient tales of their progenitors, their forefathers and mothers so many centuries ago and a secret promise made by those who were the leaders of the Jewish People who were about to enter their slave existence and who knew Joseph, the son of Jacob, also known as Israel, and, oddly, also a Prince of Egypt, to make certain to save Joseph’s bones and return them back to his homeland when the Lord would come to redeem the Jewish People from their enslavement. That is a major difference when it comes to being able to be a believer in G-d as opposed to simply being scarred by not knowing who is in charge. After all, until the Ten Commandments, there had been no pathway for the Jews to walk. There had been no Torah and its 613 commandments. There had been no kosher, no Shabbas, no nothing; except for the Seven Noahide Laws, which was the dividing line between civilized man and barbarians. So, for the Jews to be made up of individuals with varying degrees of faith in G-d, who had been all but hidden from them until then, has got to have been expected. How can we really blame them for having been skeptical about their future when we look at their past? But, that is not the same for us today who have the Torah and its Mitzvah-driven Path to follow. We may not be there with our faces all radiant like Moses was but we have to be a lot closer to that state then those who wandered for forty years in the desert until the last of them died. Though, when we remember that those last Jews of slavery were way ahead of us in the sense that they were there and witnessed the amazing miracles that G-d made happen to bring about the Exodus from Egypt; the Ten Plagues. And, these same people were there at Mount Sinai to witness Mataan Torah; the Giving of the Torah. So, how could all that miraculous firepower of G-d have been supplanted so completely as to result in not one single person from the last generation of slavery in Egypt being able to make it to the Land of Israel to stay and inherit it as was their promise to fulfill? Clearly, slavery is the factor that made that gap so wide as to be insurmountable. Slavery; we really need to think about slavery very carefully as we approach Passover.

Maftir The Maftir Alleiah for Shabbas Parah is from Bamedbar, Numbers 19:1-22 and deals with the Biblical statutes surrounding the laws of purity or defilement or, more accurately, how it is to be dealt with to bring a person back to physical purity after having come in contact for any reason or for no reason at all, strictly by accident, with a dead body. The process involving the slaughtering of a red heifer, burning to ashes, mixing the aches with water and sprinkling the water on the defiled persons to cleanse them of their defilement is detailed completely. What is not explained is what, if anything makes the coming in contact with a dead body defiling. In sentences 14-16 we learn that simply being in the same room (tent) with a dead body makes someone ritually unclean. And anything in an open vessel (like a jar) in such a room becomes ritually unclean. Even touching a grave will make a person ritually unclean. The best explanation we have heard that sheds some light on the subject of ritual uncleanness was from our teacher Rabbi Steven Shlomo Riskin back in 1966 or so at Yeshiva University when he was teaching in the then Jewish Studies Program. Rabbi Riskin pointed out that various conditions that dealt with spiritual defilement were ones where the life potential of the central person involved was no more. He mentioned, of course, the potential of a person who has died is gone. He went on to include a woman who was menstruating in that the potential for a new life that she had within her was, at that time in her menstrual cycle, no more and therefore the potential connected with that possible life is unfulfilled. He then drew a comparison to the overall purpose of the work of the Holy Temple or to its predecessor the Mishkan, which was to foster the potential of living people to realize their fullest possible potential. So, the laws of purification were possibly put in place to help us appreciate the two sets of mutually exclusive conditions: life and its wonderful potential and death or lack of life and its complete lack of potential. Interesting too is that at every step of the process of the Parah Aduma, the Red Heifer, all who do anything to advance it and the purification of the person who has become defiled, become unclean themselves and must wait for a period of time to become ritually clean again. Then too, we must not think that something is good and something else is bad. In sentence 4 of the Maftir reading, it is ordered that the Priest shall take some of the blood of the Red Heifer and sprinkle it with his finger towards the front of the Tent of Meeting seven times. In sentence 5 we are told that all of the heifer shall be burnt including its dung. The smell of the burning heifer could not have been particularly aromatic. Why does this hearken back to the unsavory scent of the Galbana, the foul smelling spice to be mixed into the potpourri in the Mishkan near where the Kohaniem, the Priests were to do their important work? The wood to fuel the fire that would burn the Red Heifer to ashes was to include certain types of wood, some of them being red in color as well as a piece of red wool. Red Heifer to sacrifice. Red wood with which to burn the sacrifice. Red wool in the mix and Red blood to be sprinkled from the sacrifice. Are we to be reading something into this or are we to just let it be there as a backdrop to the drama that ritual purification is to accomplish for us? Such is the nature of all Chukeem; statutes. The Torah gives us certain commandments for which reasons are given for them to be done and then there are those commandments, Chukeem, statutes, where no reasons for doing them are given. We are to do them simply based on faith. The Parah Aduma is such a Chok; a statute commandment with no reason given for doing it. The connection here to the main Sedrah is not the main reason this part of the Torah is selected as the Maftir Alliah, but it ought not to be ignored either. The belief required to make it into the Land of Israel for the Jews of the Exodus was something they could not achieve. The belief required to follow the commandments that are without explanation, Chukeem, may be quite another thing but they may be our litmus test to see if we are ready for the way of life that G-d has planned for us. In the way of another comparison, there are those who see a connection between the Sin of Golden Calf and the purification ritual of the Parah Aduma, the Red Heifer. Perhaps they are correct. Perhaps there is a connection. It is hard to say. The Sin of the Golden Calf seems to have emanated from a fear that the Jews of Slavery had so deeply ingrained in them that they could not escape its hold on their very being. Those of them who were guilty of idol worship certainly deserved being punished for it. But, those who had not worshiped idols, but who were still completely lacking in preparedness for freedom and who had no familiarity of what life would be like as a Jew led by Almighty G-d Himself, were so far beyond what it would take for them to ready for all this that they were out of control. Theirs was the transitional generation in the process of redemption. Every generation that came after them would be the benefactors of all that they went through before, during and immediately after the Exodus and the giving of the Torah. In that sense, the generation of the Exodus, even though it was ultimately denied entry to the Promised Land, was quite special. It would be and is up to each generation after theirs to do what it could towards achieving the will of G-d through His Chosen People. So, as we get ready to sit down to observe the rituals of the Passover Seder and to emulate what the Jews of the Exodus went through, keeping their very troubled slave mentality and mindset in mind would seem the right thing to do; to see if we are or maybe would have been able to demonstrate the extreme courage and faith that was needed to do each and everything that each of them were called up to do to prove their belief in G-d and, thereby, gain Geula; Redemption.

Haftarah The Haftarah Parah is taken from Ezekiel 30:16-38 and shines a spot light on a particular generation of the Jewish People who some how slipped so far away from the Torah-driven life that other peoples’ gods, small “g”, were so attractive to them that they began to worship them, which caused them to be evicted from the Land of Israel. Their infractions were not small. They committed child sacrifice, which was a complete and utter embarrassment to the Lord whose laws forbid such things. Other nations were aware of these acts and scorned the Jews and their G-d for having sunk so low. Ezekiel foresaw forgiveness by G-d of the Jewish People but not so much for themselves but for the restoration of the Jewish People to follow the true path of the Lord and thereby restore itself as a light unto the nations of the world. The Haftarah, in sentence 25, talks of purifying the people by sprinkling clear water on them to cleanse them from their idol worshiping ways. A terrific list of restorative experiences is given, all leading up to the world being able to see the Jewish People restored to greatness and all the nations knowing of it. Why would G-d do this unless to help mankind in general towards a more meaningful and rewarding life? Otherwise, He could have banished the Jewish People and it would have eventually been absorbed into nothingness and be gone. The Prophet Ezekiel had seven visions, which foresaw judgment of Israel, Judgment of the other nations and then future blessings for Israel. It must be made clear that when Ezekiel refers to Israel at first he is referring to that specific generation of the Jewish People who strayed so far from the Lord as to deserve expulsion from the Land of Israel. When the Prophet refers to Israel later on it is to the future generations of the Jewish People, and as ours is today, the Israel of destiny, which would then encompass all Jews. It is worth mentioning here that expulsion from the Land is a theme that repeats itself throughout the Torah. Adam Ha Reshone, the first man, and Eve went up against the Lord and their punishment was to be banished from the Garden of Eden; the Land. Not believing in or having enough faith in the Lord was the real Chait Ha Miragleem, the Sin of the Spies, and again, the punishment was being denied entrance to the Promised Land and to live out their lives wandering in the wilderness. The Promised Land is ours only if we fulfill our part of the covenantal arrangement as delineated in the Shama Yisroael declaration we make each day in our prayers. As long as we live the Torah-driven life we will be allowed to remain in the Land with all the needed support provided to us. However, when and if we should stop doing so, we will be driven out of the Land in the same way Adam and Eve were made to leave Eden; the same way the Jews in our Sedrah who worshiped the Golden Calf were taken care of; the same way Jews who believed the Ten Spies who spoke against the Lord and then cried to Moses and were exiled to wander the desert for the rest of their lives instead of being allowed into the Land of Israel, and the same way the generation of Jews in the days of Ezekiel in our Haftarah were captured by the Babylonians when the Bais HaMegdash, the Holy Temple in Jerusalem, was destroyed in 586 BCE. As ominous and disheartening as the Haftarah story of the Jewish People being driven out of the Land of Israel is, and as shocking and upsetting the details of the Sin of the Golden Calf are, the message of Shabbas Parah is, in all respects, a positive one. The Prophet Ezekiel tells of his vision of good things to come for the Jewish People. The Sedrah itself takes a very up-beat approach to the way it presents the episode of the Golden Calf. It makes it just that; an episode; and not at all an end in itself. It makes the Golden Calf part of a larger narrative of a continuum and does so in a context that is to serve as a launch pad that will start the Jewish People on a journey far more significant than even a demoralizing and outrageous happening such as the Sin of Golden Calf could ever derail. The description at the beginning of the Sedrah of the census and its special way of saving souls by meticulously not counting heads shows how much each of us counts in the scheme of things; by which we mean to G-d. The making of and working in the Mishkan and all its detail; right down to the specially mixed and selected spices, shows that everything we do is important. The big message to take away from Shabbas Parah is apparently that everything and everyone counts, which is to say, every one of us matters and everything we do matters too. The Maftir and its deeply mysterious Parah Aduma process of becoming ritually clean after becoming defiled assures us in another way that G-d cares greatly about each person by His putting in place a way to bring about individual and personal absolution; so much so that dozens of people must themselves become ritually impure for a limited amount of time so that others may become ritually revitalized. It is a communal effort with everyone doing everything that needs to be done and to be done with no explanation; just based on faith; faith in G-d. It demonstrates in terrific and minute detail that each of us is able to make the necessary adjustments in our lives to be spiritually ready to eat the Matzah and Morror on the eve of Passover in remembrance of the Pascal lamb. Though sacrifices are no longer actually made because the Holy Temple in Jerusalem has yet to be rebuilt again, our conducting a Passover Seder and eating of the Afikomen [the larger piece of the matzah broken off and saved away to be the last thing eaten at the end of the evening] is to serve as a living memorial to what our ancestors did to prove their readiness for Freedom and, ipso facto, their faith in the Lord. Preparing ourselves to be ritually or spiritually pure enough to do so today is surely as mysterious as the ritual purification process of the Parah Aduma, the Red Heifer described in our Maftir was to the ancients; completely unexplainable. Each of us must do it in our own way. But, to whatever extent we can do it, when we do, we will be as ready as we can be to eat the Passover meal as if we were the ones being taken out of Egypt by the Lord with a strong hand and an outstretched arm. We will be able to feel in our hearts the same feelings of great honor mixed with great wonderment that our ancestors must have felt as they experienced the end the 400 years of slavery that the Lord had told our forefathers would take place. Can we feel what they felt with respect to their long history and direct knowledge of the horrors and depravations of slavery? We can not. But, with as much empathy for what they must have felt as we can muster and keeping in mind what they were going through on that amazing night, we can look at the the Passover experience as our spiritual moment of truth. Yes. With the proper mind set and caring concern, each of us can be ready to eat the Matzah and the Morror; the bitter herbs, in remembrance of the Pascal lamb and, thereby, to demonstrate to the world around us, to the G-d of our forefathers and, most importantly, to ourselves, that we have the faith needed to be able to do so, in order that we will then be ready to answer the call to begin our personal and communal journey to the Promised Land, the embodiment of Geulah, Redemption.

|

Price

per Giclee Reproduction on Water resistant Canvas or 310 Gram Hahmemule Art Paper |

||||||

Size |

1 |

2

to 3 |

4

to 7 |

8

or more |

Standard Stretching |

Standard Stretching |

| 5" x 7" | $175.00 |

$150.00 |

$100.00 |

$70.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 8" x 10" | $225.00 |

$170.00 |

$135.00 |

$100.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 11" x 14" | $275.00 |

$225.00 |

$190.00 |

$150.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 12" x 16" | $325.00 |

$275.00 |

$200.00 |

$175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 16" x 20" | $375.00 |

$300.00 |

$225.00 |

$200.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 18" x 24" | $425.00 |

$350.00 |

$275.00 |

$225.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 24" | $475.00 |

$375.00 |

$300.00 |

$250.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 30" | $525.00 |

$400.00 |

$350.00 |

$300.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 30" | $600.00 |

$525.00 |

$475.00 |

$400.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 36" | $725.00 |

$625.00 |

$575.00 |

$500.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 30" x 40" | $850.00 |

$750.00 |

$675.00 |

$600.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 32" x 48" | $900.00 |

$800.00 |

$725.00 |

$625.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 36" x 48" | $975.00 |

$850.00 |

$775.00 |

$675.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 50" | $1,350.00 |

$1,200.00 |

$975.00 |

$875.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 60" | $1,800.00 |

$1,500.00 |

$1.300.00 |

$1,175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| Please Note: | ||||||

| 1. Prices are exclusive of shipping and handling charges, which will be added. | ||||||

| 2. Deliveries to NY, CT or NJ are subject to applicable Sales Tax. Please provide Resale or Tax Exempt Certificate with Purchase Order. | ||||||

| 3. All sales are subject to the conditions delineated in the Terms of Agreement for Sale and Transfer of a Work of Art. Please print and complete a for and submit it with purchase order. Thank you. | ||||||

| 4. Prices are for printing on canvas or on 310g archival art paper. unframed pieces. Please inquire if framing is desired. (646)998-4208 | ||||||

| Abstracts | Drawings | Oils | Still Lifes |

| Architecture | Jewish Subjects | Pastels | Water Colors |

| Books | Landscapes | Portraits | |

| Cityscapes | Nautical | Prints | |

Toll-Free Phone: (800)839-2929

Toll-Free Fax: (888)329-6287

| Echelon Artists | About Echelon Art Gallery | Drawings |

| Oil Paintings | Water Color Paintings | Prints |

| Exhibitions | Art for Art Sake | Helpful Links |

| Interesting Articles | Photographs | Pastel Paintings |

| Artists Agreement | Purchase Art Agreement |

| Geoffrey

Drew Marketing, Inc. |

|||||||

|