Tazria - Metzora

Echelon

Art Gallery

Oil Paintings,

Prints, Drawings and Water Colors

Tazria - Metzora

© Drew Kopf 2017

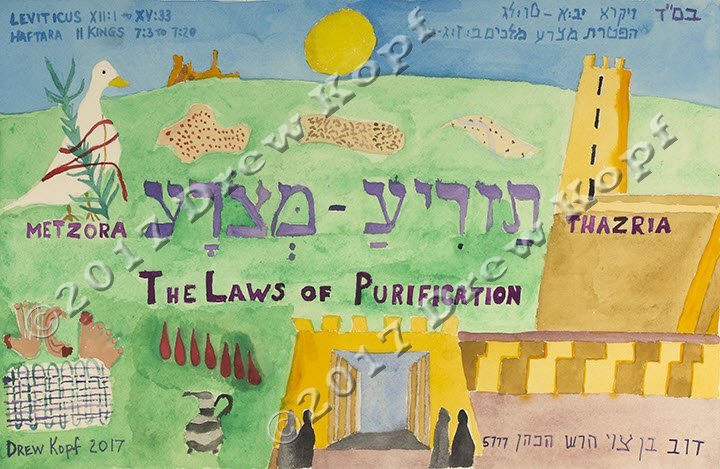

Title: Tazria - Metzora

Medium: Water Color, Marker and Graphite on Paper

Size: 12" x 15" unframed (nominal)

Available Framed or Unframed

© Drew Kopf 2017

Signed: Drew Kopf 2017 (lower left) also in Hebrew Dov ben Tsvie Hersh Ha Kohain 5777 (lower right)

Created: April 2017 corresponding to Nisan 5777

Original: Created to honor the memory of the artist's Fencing Coach and mentor Professor Dr. Arthur Tauber, z"l, 1920 - 2014 and presented as a gift of the artist to Coach Tauber's great granddaughter Stephainie Pincus on the ocassion of her Bat Mitzvah April 29, 2017 at the East Meadow Jewish Center, East Meadow, NY.

The text afixed to the back of the framed origional and which is provided with each geclee copy, reads as follows:

Combined Sedrah of Tazria and Sedrah of Metzora is the 27th and 28th in the Annual Cycle of Weekly Torah Readings. Leviticus 12:1 to 15:33 Haftara: II Kings 7:3 to 20 Foot Soldiers in the Army of the Lord by Drew Kopf

|

© Drew Kopf 2017 |

******************************************************************************************** |

| The text of this commentary is also available in PDF format. Click HERE |

Before we delve into the combined Sedrahs or Parshas of Tazria, תַזְרִיעַ, and Metzora, מְּצֹרָע, it would be helpful to see where these Sedrahs fit into the Book of Leviticus and, really, into the entire Torah, so we can more easily identify the overarching message. The Previous Sedrah of “Shmini” שְּׁמִינִי, which is translated often as “eighth” (see Leviticus Chapter 9 Verse 1 to Chapter 11 Verse 47, but which should really be referred to as “HaShmini” or “The Eighth” since this particular “eighth” is or marks the beginning of the use, which is to say the life of activity, of the “Mizbayach,” the Mishkan, which was the portable sanctuary or Temple from which all else would emanate; where the L-rd Himself would dwell among His People. So, it should be referred to as “The” Eighth” because it is, or was, clearly not just any old “eighth.” Not that it really makes much of a difference, but just to bring things up to the here and now somewhat, this “eighth” vs. “The Eighth” thing is not so much a Torah oriented point but more of a regular people oriented one. In some recent study of the City where we live, New York City, Manhattan, to be more precise, we came across some old newspaper articles dating back to the 1880’s in which “Central Park,” which had been commissioned in 1858 to be created, was constructed over the years spanning the Civil War and was finally completed in 1878, was referred to not as “Central Park,” as we typically refer to it today, but, rather as, you guessed it, “The Central Park.” Over the many years the “The” must have gotten eclipsed by the obviousness that there was no more central a park in Manhattan than “The Central Park” so to refer to it as “The Central Park” was almost being redundant. So, it was real people then who shaped things to which we may relate today as late as the way we refer to New York City’s world famous Central Park and, “LeHavdeel” – that it is to make a respectful difference in referring to things mundane in an effort to refer to things that are of a Holy nature; in this instance the Torah - to how we now shorten the way we refer to the Parsha or Sedrah of Shmini as just “eighth” instead of giving it its full honor and calling it “The Eighth.” The Parsha or Sedrah of “Shmini” deals with the work that the Kohanim, the Priests, were to do in the Mishkan, the Tent of Meeting, and defined the difference between “clean” and “unclean,” or Holy and not Holy, or Holy and Profane, or acceptable and unacceptable and it ends with the definition of living things, i.e. animals, that may be eaten and living things that may not be eaten. All-in-all, the Sedrah of “Shmini” is very special and very important since it sets forth for all time what we, the Jewish People, may and may not do, in terms of what we may eat, in the way of animals. Actually, in the Sedrah of “Shmini,” there comes a kind of dividing line between what the beginning of the Book of Leviticus, Chapters 1 through 10, and on what it focused, and what the remainder of Leviticus presents. Chapters 1 through 10 deals with the Laws of the Sanctuary, the Mishkan, the Tent of Meeting, and The Remainder of the Book of Leviticus deals with, for the most part, the Laws of Daily Life for the Jewish People. Now, as we continue reading in the Book of Leviticus at the beginning of our double Parsha or Sedrah of Tazria and Metzora, the Torah chooses to narrow its focus further still from what is permitted to us to eat; i.e. which animals may be eaten and which ones are to be considered off limits as food and even to be considered an abomination in any way, to, perhaps, the even more personal area of each person’s own individual body with regard to their being considered clean or, for some reason, defiled and, therefore, unclean, and therefore, to be isolated from the rest of the community in certain ways depending on the depth or type of defilement and what may need to be done by or to them before they can work their way back to normalcy and, then, to be, able to rejoin the community. We say “perhaps the more personal” when discussing what are certainly our very personal areas of defilement because we are supposed to “call our own fouls” to use a piece of basketball terminology. That is, we may be the only one in the world who knows that something is “wrong” with a very personal area on our body, but we are supposed to “take ourselves out of the game” until things of that nature get resolved. The Torah gets very … wait, let’s make that “extremely” detailed in how it covers the wide array of things that it considers to be abnormal and, therefore, “unclean.” But, the entire area has become a rather obscure or, what one might term, a “grey area” along the journey to where we are today. Scholars often lean away from digging very deeply into what the Torah is saying when these extremely personal areas are being discussed. Whether they view such discussion points as relating to “personal hygiene” or “health” or, if they see the situations as having to do with “religious” or “spiritual” consequences, since there is no Holy Temple extant, and since the only real consequences of a person’s personal physical aberrations would be to exclude them from having anything to do with direct contact with the Holy Temple, addressing these issues today remains, for all intents and purposes, moot. That said, commentators addressing the community-at-large will usually avoid any in depth study of these areas and allow the text to remain at the surface level so to speak. Those who dare to take on the deeper meaning of each and every physical malady, do so for a rather limited audience of elite scholars and with the knowledge that any adaptable lessons that might be extrapolated from such work could only be applicable when the Holy Temple is finally and at last rebuilt. May it be so and soon. At this juncture, and even before we visit the text in the Torah itself, allow us to share what we believe to be one of the most helpful views of these very delicate and possibly disturbing areas of Torah Law. Rabbi Shlomo (Steven) Riskin, (b 1940), who is the Chief Rabbi of Efrat, Israel, was our teacher at Yeshiva College of Yeshiva University in the 1960s, and directed our attention to a certain commonality that exists with every situation that would cause a Kohain to become defiled and, therefore, unfit to serve in the Holy Temple, until the situation had been remedied. Rabbi Riskin noted that everything with which the Holy Temple and, therefore, the Kohain Gadol, the High Priest, and, really, all of the Kohanim, the Priests, would be dealing relates to what might be termed “spiritual fulfillment,” which requires that anyone involved in some way with service in the Holy Temple as an example, would have to have what Rabbi Riskin termed spiritual potential; that is, that they must be alive and be fully able to realize their creative potential; i.e. that nothing be holding them back in any way or diminish their natural capabilities. The situations, maladies, conditions or states of being that are the underlying factors that are in direct contradiction to the mission of the Kohain Gadol and, really, any of his fellow Kohanim, is that which would represent; or, better, that which no longer has its former potential. That is where there is “unfulfilled potential” such as a dead body, a woman experiencing her menses, which means that the potential of that particular egg or those eggs can no longer be realized, or any other such situation where in a person’s potential is gone or severely curtailed. Potential vs unfulfilled potential. Rabbi Riskin reminds us or explains that the Torah is “life driven.” When a person dies, their potential dies with them. The Kohain Gadol, the High Priest, in the work of the Holy Temple, is dealing exclusively with the potential of mankind. The two conditions are in direct counter distinction with one another. The Torah does all it can to impress upon us the importance of living life to the fullest in the way of the L-rd’s Covenantal Agreement with Abraham. Let us not take for granted that we recall precisely what that covenantal agreement is. It is stated first at Genesis Chapter 15 Verses 18 to 21: Verse 18. On that day, the Lord formed a covenant with Abram, saying, "To your seed I have given this land, from the river of Egypt until the great river, the Euphrates River. There is nothing apparently required on the part of Abraham. This is a gift from the L-rd to Abraham (actually referred to as Abram at that juncture) for his having made the discovery and for having connected with the L-rd and having devoted his life to living in the certain way prescribed by the L-rd. We see the details how that life is to be lived in the Shama Yisroel, which, in summary tells us to worship no other gods (small “g”) than the L-rd. If we honor that commitment, all will be well. If we drift away and worship other gods (small “g”) then all bets are off and we will be ejected from the Promised Land. That is the deal. That is the Covenantal Agreement. If one would take nothing more than that away from the Sedrahs of Tazria and Metzora, one would have taken away quite a lot. The Sedrah of Tazria begins at the beginning in a way; with childbirth. (Leviticus Chapter 12 Verse 1) Not so much with a description of a bouncing little bundle of joy but, rather, in a manner of speaking, with the mess, natural though it may be, that is left after a baby is born. The over riding question the Torah seems to be addressing in its directions is, “when can the new mother get back to living a normal life once she has given birth to her baby?” The Torah employs a universal approach; one for after having given birth to a boy baby and the other for after having given birth to a girl baby. The Torah does not choose to elaborate on why there is a difference depending on the sex of the new baby but it is precise and definitive in its directions. Interestingly, the number “eight” play just as in the previous Parsha of Shmini (The Eighth), when we are told that on the eighth day after a mother gives birth to a boy the baby is to be circumcised. It is almost as if the circumcising of the baby has something to do with the process that the mother is to take or observe as she goes from the state of being considered “unclean” to being considered “clean” again. We are told just how many days after her having given birth she must wait and that having given birth is regarded in a similar way as if she had been experiencing her menses. When the bleeding ends, a requisite number of days is allowed to pass before certain animals are to be brought to the Priest, the Kohain, outside the Tent of Meeting, the Mishkan, and offered there as sacrifices of atonement after which she would be considered to be “clean.” Clean for what purpose; to be permitted to touch and be involved with the Holy Temple, the Tent of Meeting, The Mishkan. It is, again, interesting that even though the bleeding that took place or came as a result of having given birth to a new baby, the bleeding itself is still equated to the bleeding experienced during the period of menstruation, which would be when the potential of a new baby conceived and born would have been missed; i.e. unfulfilled. We would like to know how Rabbi Riskin would fit what seems to be a difficult situation into his explanation of “clean” and “unclean” in terms of “potential” and “unfulfilled potential.” But, perhaps the answer Rabbi Riskin might give us is right in front of us. The birth of a new baby, though launching all sorts of potential, is so only for the new baby himself or herself. But, as far as the mother is concerned, once her baby has been born, she herself is without the potential to give birth again until she will have rebounded in the time it takes for her body to return to its normal state of readiness to conceive a child. Giving birth, though wonderful and amazing and filled with all kinds of hope and expectation is, still, a happening that is separate and apart from the two people directly involved, the mother and her baby, and really divides the two who were, in a way, as one; i.e. the baby and its mother are no longer as one but, rather, two completely different people. Once born, the baby is the one with the potential and the mother, who just gave birth to the new baby, is now unable to do so until she has gone through the physical process that brings her back to normalcy from the point of view of having the potential to conceive and give birth again. Remember, please, that the Torah tells us what is to be done. But, in many cases, it does not tell us why. However, if one camps out for a while and gets in tune with what the mission of the Torah is, one can feel or discern the message and, understanding the message, may bring about an appreciation of the answer to our initial question; why? Everything comes down to where we are going and how we are going to get there; why we are here on earth at all and what it is that we will be doing while we are fortunate enough to be here. And, that has all to do with the Covenant struck between Father Abraham and the L-rd. It is delineated in the three paragraphs of the Shama Yisroel that we recite or say in the morning and evening prayers each day and before we go to sleep at night. It is inscribed on the parchments rolled up inside the Tefillin (Phylacteries) worn on weekdays during morning prayers and in the parchment rolled up inside the Mezuzahs, which means “doorposts” and which are small containers that get affixed on the door posts and gates of our homes, places of business and community institutions such as schools, synagogues and meeting halls. When we acknowledge the words penned on these parchments in some way; by kissing a Mezuzah, or wearing our Tefillin (Phylacteries) or reciting the Shama Yesroel, we are supposed to be reiterating our personal commitment to keep up our part of the Covenant with the understanding and trust that the L-rd will keep His part of the Covenant. We say “supposed to be reiterating” because it is not clear to us whether most of us who do such things do so more by rote than as an actual personal statement of his or her commitment to the Covenant. It is simple. There really is nothing very “religious” or even highly spiritual about it. There is really no need to go off into some alpha state to “get connected” to, or to feel, or to reach or to know or to anything at all … just simply do your part by living the life the L-rd has delineated for us and, in dong so, one helps the Jewish People act as a light unto the other nations (read: peoples) of the world to do likewise. It really does not get much simpler than that. After presenting the way women who give birth are to conduct themselves during their time of purification, which is to say to go from “unclean,” which according to the wisdom of Rabbi Riskin means lacking the potential that they would have were they able to conceive and give birth to a child, and, therefore, unsuited to take part or even to come in contact with the Holy Temple, the Tent of Meeting, where “potential;” i.e. life, is the main, if not the sole focus, the Torah turns to the Laws of Leprosy. Anyone who might have an ambition to go into the field of medicine will find this part of the Torah absolutely fascinating. Even without the advantages of modern day devices, such as microscopes, stethoscopes, and the like, the Kohain, the Priest, was schooled by the Torah to be able to determine what presented to them was actually within the bounds of normalcy or was, indeed, a form of leprosy, which would require the afflicted person to be quarantined outside of the camp. For the average observer, one might wonder, “Why do we need such minute detail recorded in this way and presented to be on par with everything else that the Torah shares with us?” It’s a good question. At first blush, one must know that if the Torah shares it with us, it has got to be of extreme importance. And, due to the normal tendency for people to think, “Yea, but that will never happen to me.” Most of us will just read through this section without doing much more than allowing it to register as an historical happening and, beyond that, pay little mind to it. But, there is something that needs to register with all of us about this Sedrah or Parsha of Tazria and that is our own individual role in the community. Surely, there are those nowadays who see themselves as not being joiners and who belong to no groups whatsoever. They are loners in the truest sense of the word. But, when it comes to the dangers of something as potentially lethal and devastating as a highly contagious disease, it is important to take the appropriate and proper steps to protect against the uncontrolled spread of that disease. Each of us is, at once, alone and yet also a member of the community-at-large and it is our responsibility to take the necessary measures to protect our brethren from such a calamity. The L-rd presents the methodology to be used to protect against such dangers from being allowed to spread. It is incumbent on each and every one of us to follow those procedures in hopes of protecting the welfare of the entire community. The Sedrah or Parsha of Metzora, Leviticus Chapter 14 Verse 1 to Chapter 15 Verse 33, continues the in depth presentation of the Laws of Leprosy. As we continue our study of the verses in Parshas Metzora, we should point out that it may be obvious for some and less so for others that the Torah is actually not divided into chapters or even into the Five Books of Moses, as we refer to them, but is, rather, one contiguous expansive whole. Nothing, therefore, is really to be extrapolated from the way the laws of purification after childbirth or leprosy are “divided” between one Chapter and another or even between one Sedrah and another; in this instance . There are years when the annual cycle of weekly Torah readings has the two Sedrahs in question read independently. There are other years, such as the year of the writing of this piece, 5777, corresponding to 2017, when the Sedrahs or Parshas are read as one contiguous Sedrah or Parsha. The Sedrah or Parsha of Metzora takes the purification of a person (a man) stricken with leprosy and allows us to learn exactly what was done once there was remediation. The great detail of the sacrifices that were to be brought by or on behalf of the healed leper and a description of the dramatic presentation of how the ceremony to mark the expression of thanks to the L-rd for the cleansing of the person so that he may return to normal life is spelled out completely. What is not discussed in any great detail is what happens to those who are and who remain unclean; that is, who are ill; stricken; infected; and, perhaps, doomed to be so for life. They would remain outside or, rather, on the edge of the community. That is about all that is known of such poor people. There must have been some way that they were able to secure food and necessities; to put up some kind of shelter. But we can only guess or surmise. The Torah, for some reason, does not provide very much information beyond that cleaning out the effected materials and clothing and housing elements combined with washing away effected areas on the contaminated persons seems to be about all that the “medicine men” of the day had at their disposal to “treat” those with leprosy. Some of the vegetation that was included in the purification celebration, such as hyssop, actually had a certain amount of healing power. The Torah does not give us very much in the way of what the “medicine men” knew or of how effective their various treatments actually were. We just know that disease was a factor in the lives of these people and, to some limited degree, the community and its leaders were able to do certain things to help control it and to protect the general community from contracting it. It will surely sound familiar to anyone who has lived long enough to have known the devastation caused by polio, swine flu, the Zeka or the Ebola viruses or any number of other deadly diseases. Without much effort, we should be able to learn the way the Jewish People in the dessert after the Exodus experienced this phenomenon. Truly, the situation described in the Sedrah or Parsha of Metzora is as current as today. Read it however you like. But, know that in the thousands of years separating us from the Jewish People of the Exodus, some things have not changed. At Leviticus Chapter 14 Verse 33, the Torah turns the proverbial page on the issue of leprosy by fast-forwarding to when the Jewish People would be eventually living in the Land of Canaan, which the L-rd would be giving to them to possess as part of His Covenantal Agreement with Abraham. Let us take a moment here and make sure everyone is up to speed. To whom are these Laws being addressed? The Jewish People were extricated from Egypt (that was the Exodus) and were on their way to the Land of Canaan. The most direct route to the Land of Canaan might take a matter of a few days or a few weeks perhaps. But, the L-rd had apparently other intentions for this transitional time from enslaved people to free people. There was a lot to do and much information to impart to where the trip to the Land of Canaan became a journey. It encompassed some thirty-eight years. The L-rd used the time to impart a massive amount of detail in how things were to be done. It included laws and responsibilities and instructions and guidelines and methodologies and restrictions and challenges and all were intermingled with personality conflicts and always the testing to see if the people were as ready for freedom as they needed to be to be free and be the exemplary nation the L-rd was intending for it to be for His plan for them, the Jewish People, to be a light unto the other nations of the world. Complicated and intricate and wonderful and amazing are just some of the words that might describe what was happening to this generation of the Jewish People. At the juncture where our Parshas or Sedrahs of Tazria and Metzora were being played out, The L-rd was apparently preparing the Jewish People for the eventuality or the possibility that there would be those members of the community who become afflicted with various diseases that were known to be highly contagious, totally disabling and potentially fatal. The verses at Leviticus Chapter 14 Verses 33 to 57 detail how the Kohain was to work when the Jewish People would finally be located in the Land of Canaan in permanent house to cleanse afflicted houses the same as you would expect. They scrape all the walls, remove even the stones and dump this material in an “unclean” place (whatever that is) outside of the city and even get rid of an entire house if the plague returns. And then, rebuild the house from scratch. At Leviticus Chapter 15 Verses 1 to 33, the Torah deals with the impurity of issues; i.e. the secretions of either a man or a woman that are abnormal. The Torah outlines the “drill,” which is to say the procedure, which is basically to isolate the person from everyone else by making his or her world completely off limits to everyone else. It must be remembered that his or her contamination was different than that of someone with an illness such as leprosy. The condition was not looked at as “sickness” at all, but, rather, as “uncleanness” if you will. And, importantly, “unclean” exclusively with regard to one’s being allowed to come into contact with the Mishkan, the Tent of Meeting, where the L-rd dwelled among His People. So, anything to do with either the Sanctuary or the Levites’ encampment, around it and all that it encompassed, was or would be off limits to men or women who were “unclean” in that way or anyone who came in contact with them until the effected persons cleansed themselves as proscribed in the Torah. And, here again, we can thank Rabbi Shlomo Riskin for his clarifying commentary for what the Sanctuary the Mishkan was all about and how certain conditions were in direct contradistinction to the meaning and mission of the Mishkan; so much so that they were not to be permitted to coexist one with the other, The Torah seems to leave nothing out with regard to living life with the L-rd in our midst while having the Mishkan in place by including the painfully detailed rules and procedures dealing with contagious diseases that shows themselves as recognizable and frighteningly off-putting to those who would encounter an afflicted person. The Torah goes to great lengths to help us know for what to look in terms of skin eruptions or colors; down to the color of a single hair on one’s body as an example. The Torah delineates the methods and steps to be taken to deal with afflicted persons to protect the rest of the Jewish People and to maintain the highest possible level of respect for and purity of the Mishkan, the Tent of Meeting, which is the structure in which the Holy of Holies is located and where the L-rd ostensibly would reside as long as the Covenantal relationship between the L-rd and the Jewish People remained in place. In an effort to leave no stone unturned, various commentators compare and relate the different skin eruptions mentioned and described in the Parshas or Sedrahs of Tazria and Metzora to elements in the various types of human personalities. In the Babylonian Talmud Arachim Page 16 Side A, the rabbinic sages go to great lengths to demonstrate that each of the three different skin eruption types of discolorations relates in some way and comes about as a result of the person who is suffering from these ailments because of having committed the following transgressions: “Lashon-HaRah,” which is derogatory speech; i.e. speaking evil of others. “Ayin-HaRah,” which is envy. “Sheefichat-Dameem,” which is bloodshed; i.e. murder. It is the contention of the sages that a person who speaks evil of someone else would eventually develop a skin eruption of a particular type as carefully described in the Torah. Similarly, with regard to one who is constantly envious of others or of one who is guilty of having taken another person’s life. We must be clear here. The Torah does not make these particular statements. This cause and effect relationship is entirely the interpretation of the sages whose opinions are included in the Babylonian Talmud. Do the mind and the body work that well together? Can something we do that is as horrible as to transgress certain basic tenets of our faith cause our skin to erupt in a certain type of irritation; a pimple; an open sore; a rash? We understand that embarrassment can cause us to turn red; to blush. Nervousness over something can give us “butterflies;” an upset stomach. To say definitively that skin ailments as delineated in the Torah describing leprosy are caused by a person’s conduct is certainly beyond us. But, in the interest of covering all the bases, it is correct that we include it here in our review and study of the Sedrahs or Parshas of Tazria and Metzora. The Rav, Rabbi Joseph Dov Ber (Bear) HaLevi Soloveitchik, z”l, (1903 - 1993), used what might be considered his rabbinical microscope on the subject of leprosy by zeroing in on the description of the key skin eruptions and discolorations associated with leprosy as described in the Parsha or Sedrah Tazria. Leviticus Chapter 13 Verse 2, “When a man shall have in the skin of his flesh ‘a rising’ (Sho-Am) ‘sees a ‘scab’ (Sapahat), or a ‘bright spot’ Baheret, and it becomes in the skin of his flesh the plague of leprosy, then he shall be brought to Aaron the Priest or unto one of the sons of the Priest.” The “Sees”, a raised area on the skin, is likened to “gaavah” which translates as “arrogance.” The Rav reminds us that our sages contend that arrogance lies at the root of all sin and they compare an arrogant person to an idol worshipper. (Babylonian Talmud, Sotah Page 4 side B) The Rav focuses on how even in something as basic as a religious education; there are parents who are more concerned as to the fanciness of the school than as to what their children will be learning in that school. To such parents, everything is judged in terms of various forms of measurements. The Rav points out that later in life the results of such “education” yields offspring who have no respect for the commandment of “honor thy father and thy mother” when old age comes into play, since everything to such people is judged by value, their old parents, who are no longer able to be productive, are seen as unimportant and get forgotten by their own children. It is hard to imagine, but we see it all the time. The second type of leprosy, Tazria, mentioned, “Sapahat”, is related by the Rav to the sin of loss of dignity, and identified with the Medes, the people who gave the world the wicked Haman, who was the essence of arrogance; a person puffed up with arrogance; who used flattery to get ahead, who was not at all a leader but, as the Rav described, was “weak and spineless.” The Rav points out that the word “Gah-Ah,” which means pride or honor, comes from two different root words. The word “gaavah” is arrogant pride and the Rav sees it as a form of spiritual “tazria” or leprosy. The passive form is “ge’ut,” which is actually a characteristic of the L-rd meaning grandeur as used in the Book of Psalms Chapter 93 Verse 1, “The L-rd will have reigned; He will have donned grandeur. “ We must avoid “gaavah, arrogance, like Haman, who dreamed of grandeur though he did not deserve it. There is, according to the Rav, “a dialectical tension between self-respect and self-esteem that healthy people possess, in other words, “ge’ut” and in sharp contradistinction the sort of “gaavah” arrogance, which leads to behavior like Haman’s. In its most extreme form, it leads to the sort of megalomania that characterized two of the worst tyrants and mass-murderers of recent history; Stalin and Hitler. (Dorosh Darah Yosef – Discourses of Rav Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchick on the Weekly Parsha by Rabbi Avisha C. David, Urim Publications, 2011). The third type of Tazria Leprosy, “Baheret,” is compared to the sin of Superficiality. The Rav tells of how the Greeks were more interested in form than in content. How a person “looked” was the big thing to the Greeks and not at all important to them was how a person “felt.” Judaism was and is more interested in the inner essence rather than in the outer beauty of something. Then, to tie a kind of bow around the issue of superficiality vs. deep significances, the Rav discussed how … not his words, “talk is cheap!” He tells of how there are those who talk a good game but do little to back up their fancy words with meaningful action. The Rav mentions his own grandfather, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, z”l, (1853 – 1918) also known as Reb Chaim of Brisker, who only gave a public presentation twice a year; on Shabbas HaGadol, the Shabbas before Passover, and on Shabbas Shuvah, the Shabbas during the Ten Days of Repentance. Yet, he was a powerful pedagogue who had profound and long lasting effect on the Jews of Brisk. The Rav sites several other examples of great and learned leaders in and of the Jewish community; even back to Moshe Rabbanu, Moses, himself who were big on action and less on making big speeches. It is the Rav’s prayer as he brings his thinking on the matter of leprosy and of what the various forms of it can be seen to indicate to a conclusion for us, that Jews in today’s world talk-the-talk but also walk-the-walk; that is if they say, “Next Year in Jerusalem” that they make it happen; to go there; to Israel. The Rav’s prayer hopes for the ending of what he calls “spiritual tazria” where, going forward, we mean what we say and say what we mean. That we keep our modesty in the forefront while boldly advancing with worthy deeds to enjoy life while also helping others, who may not be as able to do so for themselves on their own. Mazria through the eyes of the Rav. The Rav notes the obvious for us; that the Kohanim, the Priests, who are usually completely reserved and apart from anything that is ritually “unclean;” i.e. “Tah-May,” here in Parshas or Sedrah Metzora and in the previous Sedrah or Parsha Tezora, are tasked with determining everything about leprosy related diseases and to decide what was to be done with and for anyone who became afflicted with the disease or diseases related to this malady; which is to say they were to be as close to things “unclean” or “Tah-May,” as one could be without actually coming in direct contact with it. The Rav then helps us understand the apparent contradiction; the Kohanim, the Priests, need to be “spiritually clean” in order to serve in the Mishkan, the Holy Tent of Meeting, and yet be the ones who deal with the antithesis of being clean; i.e. to help those who are stricken with leprosy. It is important to understand how a person stricken with leprosy lived on a day-to-day basis and, at the same time, to know to what extent the Torah; which is to say the L-rd encouraged others, who were not so stricken, to do what could be done to help these poor unfortunate people retain at least a certain amount or level of self-respect and a feeling of self-worth. The Rav provided proof from two selections in Leviticus. One, Leviticus Chapter 13 Verses 44 to 46, that describes the deplorable and trying way people with leprosy were forced to live, i.e. outside of the encampment and completely at the mercy of the community for food and sustenance; and, Two, Leviticus Chapter 13 Verses 2 to 3, where we learn that the lepers were able to see the Kohain, even the Kohain Gadol, the “High Priest,” almost at will, even if, by necessity, outside of the encampment of the Jewish People, but still, they were a very high priority to the Kohanim, the Priests, and not at all ignored. With the help of the Ramban, Nachmanidies, Rabbi Moses ben Nachman, z”l, (1194 – 1270), who commented on Exodus Chapter 18 Verse 15, the Rav observed that the Kohanim, the Priests, were cast in the combined role of both priest and to some degree as prophet. But, more than that, with regard to people with leprosy, the Priests, the Kohanim, and even the Kohain Gadol, the High Priest, himself were the ones who served as the medical diagnosticians, nurses and judges of ritual purity and impurity. It is hard to image anyone with such a wide ranging responcibility in today’s society. The Rav concludes that there is a kind of connector piece that links the Kohanim, the Priests, whose task is always to serve and the prophets, who hear the will and intention of the L-rd and do what they can to convey this rare and crucial knowledge to the people. The common denominator between Priests, the servants of the L-rd, and Prophets, the messengers of the L-rd, is the absolute and complete commitment to help everyone; all people, Jews and non-Jews, even enemies of the Jews, without regard to who a person may be in the world; since everyone, every single person, is as important as an entire world. And, there, in what might be one of the most unlikely ways of comparing and contrasting the roles of personages in our wonderful world, we see the making of a “take away message” from the two Sedrahs or Parshas of Tazria and Metzora, that, at first glance, might look more like the inside of a biology laboratory experiment or a battle zone in a leper colony. We meet people on both ends of the “spiritual fulfillment” spectrum. The leper, who stands at the lowest rung of the “ritual purity totem pole” and the Kohain Gadol, the High Priest, who is is at the virtual top of the purity ladder. Each is mandated in the exact same mission in life, to do what ever they can on behalf of the community and to do so one soul at a time. Haftara Metzora The Haftara for the combined Sedrahs of Tazria and Metzora is the one used for the Sedrah of Metzora when the two Parshas or Sedrahs are read separately and tells of an incident in the life of the Prophet Elisha, who was known as a person who did all he could to help people who were in need, during the siege of Samaria by the Arameans. II Kings Chapter 7 Verses 3 to 20 was chosen by the rabbis to be the Haftara for Shabbas Tazria-Metzora apparently because of it’s having people stricken with leprosy in the story. Leprosy, as we saw earlier, is a major part of the Parsha or Sedrah. The Haftara opens with four men who are stricken with leprosy located near the entrance to the gate of the city of Samaria, a Jewish enclave. Looking back at Leviticus Chapter 13 Verse 46, we recall learning that lepers were almost entirely excluded from society and were forced to live outside the city. One would guess that such people would stay close to the gates of the city in hopes of obtaining food. The quick story of the Haftara is that the four men located outside of the gate to the city reason that the city is experiencing a famine and all its inhabitants and, therefore, they as well will starve to death in due time. The four men debate the possibility of going to the Arameans, an enemy of the Jewish People, to seek food since there was absolutely no possibility of finding sustenance where they were. They realized that they might be killed by the Arameans, but they reason that doing something that will give them even the smallest chance of survival makes more sense than staying where they were and having absolutely no chance of survival. Then, something that must be seen to be a miracle occurs. But, first, what is a miracle? Someone once explained that the various “miracles” in the Torah can each be explained as natural phenomenon; that is, something that could and actually does happen in real life; i.e. in nature, from time-to-time, but, what makes it a miracle is the timing; that the natural event happened there and then; when it was most needed. “Who writes this stuff?” we might ask. The answer would be HaShem, (which means “The Name” and is a respectful way of referring to the L-rd without actually saying or, in this instance writing out an actual name of the L-rd in any way that might be considered to be frivolous); the L-rd writes it. What was needed right there and then in the story of our Haftara was a perfectly timed natural occurrence. And, here we learn that, when the four diseased men arrived at the Arameans’ city and, while they were surely praying not to be killed and were hoping to be given some food for which they were, by then, desperate, they find the enemy city completely abandoned. Empty. Open. Deserted. Amazing. It was a miracle. One thing leads to another and the four leprosy stricken men find food in various dwellings, which they eat until they are satiated. They also discover certain valuables left there by the Arameans, who had left in great haste, perhaps items made out of precious metals and gem stones, which the four men take time to secret away so they will be able to access them later. We can certainly appreciate why they would do that since, being lepers, they would never be welcomed back into any city until they became cured, which might never happen. However, with a cache of valuables, such as the ones they found and saved away, they would have a much better chance of obtaining food than without such treasures at their disposal. The four lepers then decide to return to Samaria to inform the people of the existence of food nearby and they do just that. In the Stone Edition of the Chumash (The Five Books of Moses) page 1172, © 1995 Mesorah Publications Ltd., commentaries are sited but without specifically naming the commentators who authored them, that are critical of the four men stricken with leprosy, because of their having waited before going back to Samaria, the Jewish walled city, and, instead, having eaten until they were satiated and also having secreted away various valuable items, that could be used for purchasing food, as we mentioned earlier. We can understand such criticism but, at the same time, we can see exactly what motivated these men to do what they did and in the way that they did it. It is easy to be critical from our vantage point centuries later and reading of the occurrence in a nice comfortable and well lighted building with our next meal guaranteed. It should be remembered that these four men were more than just hungry. They were so desperately hungry that they went to their enemy’s walled and gated city of Aram, a people who pursued and was a sworn enemy of the Jewish People, throwing caution to the wind in hopes of receiving food enough to live for even one more day. Then, after they had satisfied their own hunger, they noticed the above mentioned valuables that they reasoned they could use once normalcy returns and they will be, again, forced to remain outside of the city with no means of support. That kind of thinking on their part demonstrates that they were thinking in the “right” way; morally speaking, right from the start. They were already thinking that they would go back to their home city to have the Jewish People, their people, come to the Arameans city to be saved by the food that was so miraculously available food in the abandoned Arameans city. But, the four men realized that, once back to normal, they would do well to have secreted away a storehouse of valuables that could later be used to purchase food or other needs. This is a good juncture to explain precisely why what these four diseased men did with respect to eating the food they found at the Arameans city and, even, what they did with the cache of valuables that they came across in that city, instead of going first to their “home” city of Samaria to alert their brethren, who were admittedly in dire straights and in need of food due to the siege and the resulting famine, was absolutely the right thing to have done. Anyone who has flown anywhere on a major public airline is familiar with the brief presentation that the flight attendants deliver before takeoff. They explain everything that could happen in the event of an emergency. They point out the exits, the lights on the floor and, in particular, they explain that oxygen masks will automatically drop down from the overhead compartment and they go on to show the passengers how to adjust the little strap that goes around your head and, most importantly, and very much to the point regarding our Haftara, the flight attendants make it very clear that in the event of an emergency, you should make sure to take care to put your oxygen mask on first before helping those in your care, such as children or the elderly. Take care of yourself first; you first and then others who may with you. With that in mind, to criticize those four unfortunate souls for not having gone straight back to Samaria to inform their people that relief from the terrible famine was nearby is really judging them far too harshly. They actually did exactly the right thing. They took care of themselves first so they could then take care of others, which they then did without any further delay. And now, we need to ask the question in a different way. Why did the leadership of the Jewish People in Samaria continue to wait as the famine brought them and the entire community closer and closer to starvation and death? Why did they not take some kind of action to seek a means of survival? Why did they just continue to wait when just waiting would mean certain death? We understand that their city was under siege by the Arameans. But, if four starving men stricken with leprosy reasoned that it would be wiser to take a chance and ask for aid and food from their enemy and risk being killed out right than to just wait and die of starvation, why were the leaders and the other people in the Community unable to do the same? That is the real question we need to ask. If we are going to be critical of anyone, perhaps we should start with the king of the Jewish city of Samaria. Even when the news of the abandoned city of Aram is brought to his attention he cowers in fear that they are being tricked and that there really is no food and that it is all just a trap. Eventually, he concedes and allows his people to go out and take advantage of the amazing situation. Amazing situation is .. Wait just a cotton pickin’ minute. It was an outright miracle. Of course, having not read Verse 1, we would not know that there even was a Prophecy made by the Prophet Elisha and, thereby, this “amazing situation” of the abandoned city packed with food and all sorts of treasures would qualify as much more than an “amazing situation” but an absolute and outright miracle. With some delay on the part of the king, who is distrustful of the situation and only believes it is true after sending out a test group to see if the facts were indeed as reported and that salvation, food, is near by and available. Once convinced, the king allows all the people to go to the Arameans’ city to find food and save their lives. The story then tells of a certain captain in the king’s service, who apparently had spoken out against the possibility of there being food coming out of nowhere, just like this, so to speak, who gets knocked to the ground by the desperate people making their way to the food of the Arameans and that the captain actually gets inadvertently trampled to death by the crowd. The story about the captain gets repeated in the text and illuminated upon which explains how the captain had actually been disrespectful to the L-rd in the way he denounced the possibility of food coming to the Jewish People in this or any way at all and the text shares that the very amazing and impossible way that the captain had said could and would not occur, actually did occur and that, as a direct result, the captain got trampled upon by the people in their great rush to food and he died. That is the tale told quickly. But, something here is very odd. The Haftara, as prescribed by the rabbis, is II Kings Chapter 7 Verses 3 to 20. Why did the rabbis decide to leave out II Kings Chapter 7 verses 1 and 2? Does any one discuss this? Let us take a few moments to review what our rabbis chose to omit from the Haftara for this admittedly unusual Parsha or Sedrah of Tazria –Metzora to see if something shows us why these two verses were not included by the rabbis. II Kings 7: verse 1 – “And Elisha said: ‘Hear ye the word of the L-rd; thus saith the L-rd: Tomorrow about this time shall a measure of fine flour be sold for a shekel and two measures of barley for a shekel, in the gate of Samaria.” What about these two verses make them unsuitable or unnecessary for inclusion in our Haftara? Or, in other words, “Why did the sages choose to exclude these two verses from our Haftara?” Elisha announces the end of the terrible famine and the coming of a supply of an amazing amount of grain. He not only predicts the end of the famine but says the end of the famine is coming tomorrow. That, one must admit, was extremely bold. But, it is in line with our definition of what a miracle is; natural things that could happen but at the exact time they art needed. We then learn of a captain who remains unnamed and who is apparently very close to the king in his service since the king is said to “lean on his (the captain’s) hand.,” and to, or with whom, we are would have been to the king and in the presence of Elisha. The captain’s comments are motivated by several things. One, he is suffering from the effects of the famine as is everyone else; Two, he is, even as a captain in the king’s service, a subordinate to the king and, very likely, not one to be critical of anyone for whom the king has a great deal of respect, which, we would guess, is the case in this instance with Elisha and, Three, he regards the prediction of Elisha from his own very limited perspective and gives absolutely no credence to the prophet’s prediction or pronouncement and; basically, pooh-poohs it completely. Elisha’s remarks not told, the captain shares or addresses mocking and even scornful criticism of Elisha’s predictions. We can surmise that the captain’s disrespectful remarks after the captain’s vile, unnecessary and demeaning remarks are what might be seen as a secondary prediction or prophesy; i.e. that he, the captain, will get to see how wrong his (the captain’s) statement really was, but that he will not get to allay his own feelings of starvation since he will not be given the opportunity to eat the food that will come in such plenty on the following day. Elisha was not just predicting something akin to which team would win a championship game. The famine was so severe that one who would not be able to “enjoy” the benefit of eating when food would finally be available would not just be proven wrong when Elisha was proven to be right; they would not survive the ordeal. How the captain would actually die is not revealed at that juncture, but, that he would die was surely indicated in Elisha’s comments following the captain’s negativity. The rabbis, in selecting a Haftara to echo the message or lesson of the Torah portion of Metzora have us read past the first two verses of the story of the miracle predicted by the Prophet Elisha. They were apparently not interested in bringing to our attention the scornful and disrespectful attitude of the king’s captain or even of the king himself, who says nothing in support of Elisha’s announcement and prophesy and just, apparently, accepts the captain’s criticism as worthy on its face. The rabbis begin our Haftara instead with Verse 3 which makes an immediate connection between the Torah portion and that deals with leprosy and the four men in the Haftara who suffer from leprosy but, who apparently do not allow their condition to cloud their thinking nor to diminish their appreciation for life and their willingness to do whatever they can to give themselves a chance to keep on living. If the Haftara had started and ended with the Prophesy of Elisha, our focus would be on G-d and His ability to perform miracles; i.e. to deliver a very much needed but, still, a natural eventuality, but with exquisitely executed and perfect timing, it would be glorious of course, and our lesson for the day would be … Right. The rabbis are clearly asking that we focus not on Elisha’s prophesy nor on the miracle, but, rather, on those four humble men who, for whatever reason or reasons, were each stricken with leprosy and relegated to living on the outer edge of the Jewish Community, for fear of allowing the rest of the population to become similarly stricken with the same ailment, but, still, as valued members of the community with the hope of becoming cured and, then, when they would finally be returning to a normal life within the community, and, more importantly for us today, what we would do if we were in their position. Beginning the Haftara at Verse 3 narrows our focus to these four men and their immediate and very desperate situation. But, each of us must ask ourselves, “What would I do if I were in their position?” One would hope that we would do exactly what they did. They saw the proverbial writing in the wall. They were doomed if they stayed where they were. They reasoned that doing something; even something that under normal circumstances would be highly dangerous or even potentially fatal, would be better than doing nothing at all. Was what they did based on faith? That is a good question. But, at this juncture, they were not so much being tested as they really had only two choices; to take a chance on their enemy being of a new mind and open to helping them or staying where they were and starving to death along with everyone else in the Community. But, in choosing life and in helping themselves to whatever extent they could, they serve as an example of what our own values need to be; to choose life. And here, after asking ourselves, “What would we have done in their position?” we can, perhaps, learn a lesson for getting the most out of each and every day, whether faced with such grand and earthshaking decisions as the four protagonists who we met in II Kings Chapter 7 Verse 3, or on just what one might call a regular day. We see that if the four lepers had not been where they were and did not reason as they did, the Jewish Community, even with the life saving food they needed being right down the road, so to speak, would have apparently stayed their ground and starved to death. But, the four men on the outer edge of the community were still part of the community and were clearly still committed to and thinking as individuals on their own to stay alive and to save their brethren. The tremendous importance of each and every one of us is very much a focus of this story; particularly as the rabbis have presented it, without Verses 1 and 2 included. Just as the Kohain Gadol, the High Priest, served everyone and did not at all ignore even the leprosy stricken people on the edge of the community, each of us is to be as a priest, a Kohain, to the world and must do all we can do to help others in any way that we are able. When I meet someone who is currently a member of or is a veteran of the US Armed Forces, it is my practice to take a moment to acknowledge their having devoted their time and effort on behalf of our country by thanking them for their service. As I thank them, I inevitably think back to my father and my teacher, Harold Kopf, z”l, (1920 – 1996), who served in the United States Army during World War II. I bring this up here because of the word that links our Sedrah and all those, like my beloved father, who were in one of the US Armed Forces. Thank you for your service. They served. Service is the common denominator. And, as we see in our Sedrah, service is what the Kohanim in Judaism are all about. Similarly, it is ostensibly the goal of all Jews to live the life proscribed in the Covenantal Agreement with the L-rd wherein we agree not worship other gods (small “g”) and, in doing so, to serve as a light unto the other nations of the world. My father told me that a, if not the, major difference between how the US Army, and surely the other services as well, functioned as compared to the way the enemy armies did during World War II was in the way mission objectives were executed. The enemy armies’ leadership knew the objectives and issued orders to the troops to accomplish the goal or goals. The officers knew the details of the plan. The soldiers knew nothing. The consequences of that methodology when an officer was unable to perform his duties for some reason would invariably be the complete and immediate breakdown of the unit. The Americans shared mission details with everyone in the unit right down to Buck Privates and even with the cooks, so that if and when something would happen to the leader or leaders of a unit, the mission would continue to be advanced. If there were two or three Privates who were left in or cut off from their unit, they knew by their enlistment dates which one of them was the “ranking” man who was to serve as unit leader and who would make the decisions that would have to be made to do what needed to be done to accomplish their unit objectives. What does this mean to us when we think about our community today? The four leprosy stricken men in our Haftara could have been anyone in the community. Their decisions and resulting actions in light of the dire situation in which they found themselves saved the entire community from starvation. Surely, the L-rd stepped up and delivered on the prophecy of Elisha by “chasing’ the Armenians away and, thereby, provided food just when it was needed. But, it was those four unnamed men pushed to the edge of the society by leprosy who saw themselves as still part of the community and were willing to do whatever they could to save their own lives and, then, to do the same for the rest of the Jewish Community. They were each comparable to soldiers in the US Army in World War II who knew the mission and did what needed to be done to accomplish it. Our prayer is that each of us be as committed to our community and to the world-at-large as any of the four unidentified men we meet in Verse 3 of the Haftara of Tazria and Metzora and that we each serve as, what my father would call, a foot soldier in the army of the L-rd and, in the way of the Kohain Gadol, the High Priest, who took time to care for any and all who may have needed his help, and, through such caring and helping, that our service be seen as a light to the other nations of the world.

|

| The text of this commentary is also available in PDF format. Click HERE |

Price

per Giclee Reproduction on Water resistant Canvas or 310 Gram Hahmemule Art Paper |

||||||

Size |

1 |

2

to 3 |

4

to 7 |

8

or more |

Standard Stretching |

Standard Stretching |

| 5" x 7" | $175.00 |

$150.00 |

$100.00 |

$70.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 8" x 10" | $225.00 |

$170.00 |

$135.00 |

$100.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 11" x 14" | $275.00 |

$225.00 |

$190.00 |

$150.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 12" x 16" | $325.00 |

$275.00 |

$200.00 |

$175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 16" x 20" | $375.00 |

$300.00 |

$225.00 |

$200.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 18" x 24" | $425.00 |

$350.00 |

$275.00 |

$225.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 24" | $475.00 |

$375.00 |

$300.00 |

$250.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 30" | $525.00 |

$400.00 |

$350.00 |

$300.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 30" | $600.00 |

$525.00 |

$475.00 |

$400.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 36" | $725.00 |

$625.00 |

$575.00 |

$500.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 30" x 40" | $850.00 |

$750.00 |

$675.00 |

$600.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 32" x 48" | $900.00 |

$800.00 |

$725.00 |

$625.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 36" x 48" | $975.00 |

$850.00 |

$775.00 |

$675.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 50" | $1,350.00 |

$1,200.00 |

$975.00 |

$875.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 60" | $1,800.00 |

$1,500.00 |

$1.300.00 |

$1,175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| Please Note: | ||||||

| 1. Prices are exclusive of shipping and handling charges, which will be added. | ||||||

| 2. Deliveries to NY, CT or NJ are subject to applicable Sales Tax. Please provide Resale or Tax Exempt Certificate with Purchase Order. | ||||||

| 3. All sales are subject to the conditions delineated in the Terms of Agreement for Sale and Transfer of a Work of Art. Please print and complete a for and submit it with purchase order. Thank you. | ||||||

| 4. Prices are for printing on canvas or on 310g archival art paper. unframed pieces. Please inquire if framing is desired. (646)998-4208 | ||||||

| Abstracts | Drawings | Oils | Still Lifes |

| Architecture | Jewish Subjects | Pastels | Water Colors |

| Books | Landscapes | Portraits | |

| Cityscapes | Nautical | Prints | |

Toll-Free Phone: (800)839-2929

Toll-Free Fax: (888)329-6287

| Echelon Artists | About Echelon Art Gallery | Drawings |

| Oil Paintings | Water Color Paintings | Prints |

| Exhibitions | Art for Art Sake | Helpful Links |

| Interesting Articles | Photographs | Pastel Paintings |

| Artists Agreement | Purchase Art Agreement |

| Geoffrey

Drew Marketing, Inc. |

|||||||

|