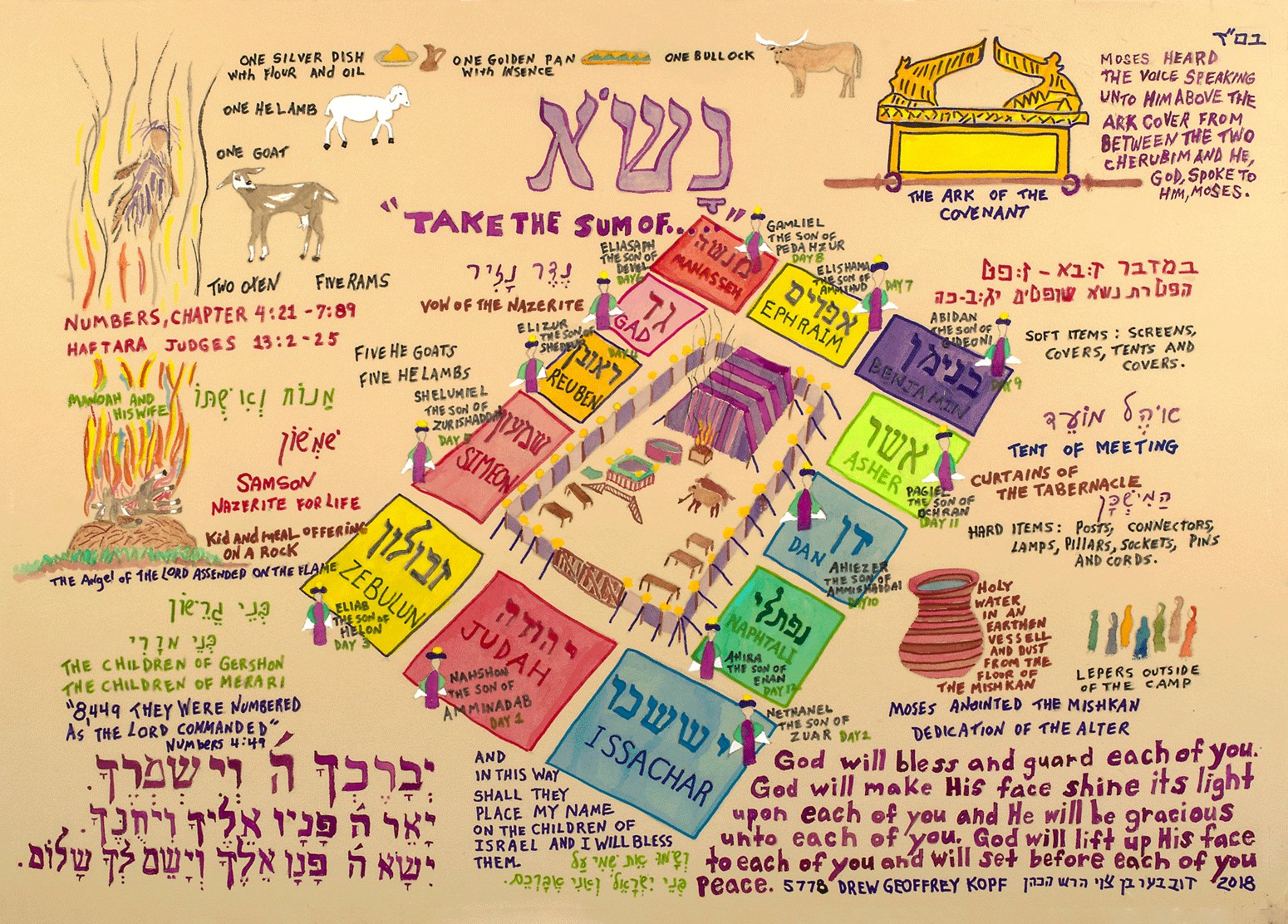

Sedrah of Naso

Echelon

Art Gallery

Oil Paintings,

Prints, Drawings and Water Colors

Sedrah of Naso

© Drew Kopf 2018

Title: Sedrah of Naso

Medium: Water Color, Marker and Graphite on Paper

Size: __" x __" unframed (nominal)

Available Framed or Unframed

© Drew Kopf 2018

Signed: Drew Kopf 2017 (lower left) also in Hebrew Dov ben Tsvie Hersh Ha Kohain 5777 (lower right)

Created: July 2018 corresponding to AV 5772

Original: Created to mark the becoming of a Bar Mitzvah of Aaron in White Plains, NY.

The text afixed to the back of the framed origional and which is provided with each geclee copy, reads as follows:

| The text of this commentary is also available in PDF format. Click HERE |

Actions Speak Louder Than Words Sedrah Naso In our day and age, it is not uncommon for us to hear adults asking little children, “What are you going to be when you grow up?” After all, it is a fair question. Whether one wants to become a teacher, a carpenter, a doctor, an artist or a baseball player, doing something to help others in the community and, through one’s efforts, to earn a living, is something each of us hopes to be able to decide for ourselves and to even, perhaps, adjust along the way if necessary in order to afford ourselves the most possible pleasure from what we do as we live out our lives. In Kohelles (Ecclesiastes) Chapter 3 Verse 22, King Solomon reports that “I have seen that nothing is right unless a man enjoys his creations.” But, we can see here, in the Sedrah of Naso, where the Torah continues to focus on the myriad of duties and tasks involved in the caretaking and transporting of the Mishakan or the Tent of Meeting, which is also referred to as the Tabernacle, that this idea of, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” was not at all part of one’s life agenda when the Jewish People were evolving after the four hundred years of slavery in Egypt had finally ended and Redemption was at last in progress. Our Sedrah opens with the Torah telling us that G-d spoke to Moses with regard to B’nai Gershon; the sons, or it could be translated as the children of Gershon, in terms of zeroing in on a figure that would give them an idea as to how many people made up that family at that time and, at the same time, delineating what responsibilities that “family” would have with regard to the Mishkan, the Holy Temple, which is the Tent of Meeting. The Torah, in this instance, requests that a kind of census be taken in that it asks that the able-bodied men from thirty to fifty years of age be counted as they would be the ones who would be designated to specialize in all things related to transporting the Mishkan as it is taken down, ported along the way and then reassembled in its next location. Granted, it might be possible to interpolate from the numbers counted approximately how many people both younger and older than the target group and perhaps even the number of women, but that was not the objective of the Torah at this juncture. And, we might add that it was clearly not the need of the L-rd to learn or to determine the population data being sought. But, rather, it was the Torah giving the Jewish People of the day a way to gain an understanding of their community using numbers of people who will be doing certain relevant and important work in support of the entire community and, perhaps, or hopefully, establishing in them an understanding of the level of importance of the work that they would be doing. The Torah, in Numbers Chapter 4 Verses 25 to 28, details the items with which the children of Gershon were to be responsible to carry and protect. The Torah does not mention the word “protect” as such, but one can easily appreciate how the way the people who would be handling and working with the various physical elements that made up the Mishkan would do that work could have an effect on how those elements would fair and look each time there were packed and, later, unpacked and reassembled in a new location. One would hope that the children of Gershon who were directly involved in the work needed to dismantle, pack, port, unpack and reassemble the soft elements that made up the Mishhkan would be aware, or should we say be well aware, of how key those pieces were to the overall mission of the Mishkan and, therefore, would have taken great care to protect the physical integrity of the materials with which they would be working as each episode of the march through the desert would progress from encampment to encampment until they would reach the Land of Canaan; the Promised Land. Would they have the same kind of commitment to their various tasks that a person might who was able to choose the kind of work they would do “when they grow up” as youngsters today, who have that choice? It is an interesting question. On September 16, 1940, the United States instituted the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, which required all men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft. This was the first peacetime draft in United States' history. Those who were selected from the draft lottery were required to serve at least one year in the armed forces. Once the United States entered WWII, draft terms extended through the duration of the fighting. By the end of the war in 1945, 50 million men between eighteen and forty-five had registered for the draft and 10 million had been inducted in the military. They would have to be “able-bodied,” which was determined by a physical examination or proof from a person’s medical history, before they would be inducted in to the service. Such a program is still in existence in the State of Israel where some kind of military service is required of all young people after being graduated from high school. There is a thought that some kind of mandatory “community service” instituted in the United States, which would require a kind of “gap year” or two when high school graduates would perform various duties or services that would aid or protect certain segments of the society, before going on to college or out into the work force. There would be dispensation for those who would opt to join the armed services, perhaps, or certain ways to allow those who might complete college and dedicate a certain amount of time to various types of endeavors that, again, would aid the community-at-large, such as teaching or legal aid, counseling, nursing or the like. Following the stock market crash of 1929, which nearly one hundred years ago now, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt instituted several national work and community relief programs that gave people employment opportunities when there was no work to be had. People were literally selling pencils and apples in the street, or standing in bread lines or begging for food. The programs included The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), The Civilian Conservation Corp. (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA). We, today, are actually the beneficiaries of many of those programs; witness as an example the Bethpage State Park, built in 1936 by the CCC on Long Island. Enrollees in the CCC planted nearly three billion trees to help reforest America; constructed trails, lodges and related facilities in more than eight hundred parks across the nation and upgraded many state parks, upgraded forest fire fighting methods and built a network of service buildings and public roadways in remote areas. The advantages of such community based service programs would hopefully include a fortified feeling of connection to the community-at-large at a young enough age where the result would hopefully be a lifetime affiliation with, to and for one’s people. It might be a bit of a stretch for us to compare the difficult times of the “depression” in the United States of the 1930s to the slavery mentality of those who had slavery in their family history for four hundred years and who now were about to be redeemed by the L-rd. But, let us try. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” may be a nice thing to ask a little kid these days, but, at the time of the Exodus, when slavery was what had been a Jewish person’s only prospect for the future of his or her life, there was no possible sense of wanting to “be” anything in particular in the way of a career for a young person of the day. They simply wanted to be free and safe. We need to keep that in mind as we continue reading the Torah at this juncture. When all those men between thirty years of age and fifty years of age are virtually “drafted” to the service of porting the Mishkan from one location to the next, it can be likened, “Lehavdeel,” to the “work” opportunities that were provided to those who were so down on their luck during the “depression” of the 1930s in the United States, which gave them what to do that would be helpful to the community-at-large and to give themselves a living wage at the same time. (“Lehavdeel” means to make a distinction as to “divide” one from another, so, in this instance, to distinguish something from something else when making a comparison. In this instance, the “Mishkan” serves a holy purpose where the various work opportunities and institutions created during the “depression” in the 1930s was a mundane purpose but, had certain aspects that could be likened one to the other. In this instance that those, so in need of work and really a purpose for living, were well served by the services provided for them to perform in one instance by FDR (President Franklin D. Roosevelt) and, in the other, by the L-rd. “Lehavdeel.” We might take a moment here to probe a little deeper into the Gershonites, as they may be referred to in English, and to their responsibilities based on what the Torah has told us regarding their work involved in transporting the soft elements of the Mishkan from one location to the next. We can recall quite easily the list of the pieces and parts of the Mishakan that needed to be disassembled, carefully packed for transporting and reassembled in the next stop along the journey through the desert to the Promised Land. Later, however, after the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” (The Sin of the Spies), which we will learn about in Numbers Chapters 13 and 14, the generations of the “Miragleem” (The Spies) who live out the last days of their lives wandering aimlessly through the desert, end up actually being the very people who were the ones who were counted in the census of the Sedrah of Naso. So, in a way, the events on the Sedrah of Naso are setting the scene for those forty years of wandering through the desert. The Torah does not have us look forward to the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” (The Sin of the Spies) here, but, when we realize that the Jewish People, who will be wandering around in the desert just waiting for that generation of the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” (The Sin of the Spies) to die as their punishment for their complete lack of faith in the L-rd, can justify our doing so. The Torah, in Numbers Chapter 13 Verses 1 to 33, describes the entire episode that led up to and resulted in the wandering of the Jewish People through the desert for forty years. The “Miragleem” (the Spies or Scouts) were the twelve Princes of the Jewish People, each selected from and representing one of the Twelve Tribes, who were tasked with the mission to scouting out or spying on the Land of Canaan and the Canaanites as well as the other peoples who were living there. The Jewish People, who had been enslaved in Egypt for four hundred years, were in the process of being redeemed by the L-rd. But, before simply advancing on the Land of Canaan and contesting for it with the, then, current inhabitants with the object of making that land their own as previously promised by the L-rd to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; i.e. The Promised Land. Frankly, if the Jewish People of the generation of the “Miragleem”; i.e the ones who had actually been slaves in Egypt, had had a certain level of faith in the L-rd, there would have been no need to have had the “Miragleem” spy out the Land at all. The Jewish People would have advanced on Canaan – the people and the land – and the rest would have been history. But, that was not the case; not even close to it. Two of the Spies, Joshua and Caleb, brought back a positive report; “Land flowing with milk and honey,” but the other ten spies, thought they did agree with the evaluation of the Land as being beautiful, testified that the people who lived there were “giants” and would decimate the Jews should they challenge them for the land; i.e. attack them. Even though Joshua and Caleb were of the opinion that the Jews could defeat the Canaanites, the People; i.e. the Jewish People gave credence to the ten naysayer spies and cried out to Moses that they would have been better off had he, Moses, not taken them out of Egypt only to die here in the Land of Canaan. That was the proverbial “last straw” for the L-rd. He, the L-rd, was about to kill that entire generation of the Jewish People for their complete lack of faith in the L-rd and, then, to start all over again with Moses. But, Moses begged for lenience and G-d acquiesced by allowing the Jewish People to wander in the desert until the last of “that” generation had died before leading the next generation into the Land of Canaan; the Promised Land. We, today, actually live with “reminders” of the “Chait Ha Miragleem” (the Sin of the Spies) to the extent that we may or may not come in contact with or even just know and be conscious of the Ten Men (persons in some segments of the Jewish Community) needed for a “minyan” (the quorum required for certain prayers to be recited) and the “Kot Aidus,” the two witnesses, needed in a Bais Din (a Jewish Court of Law) or in dealing with situations where witnesses are required; like at a wedding ceremony where the “Katuba” (the wedding contract) must be signed by two witnesses as must the “witnessing” of “Yechude,” which is where the couple being married are observed by two witnesses who can testify that the couple was indeed together in a room alone for a sufficient amount of time for the couple to have consummated the marriage. The “two witnesses” comes from the two Spies who spoke in support of the L-rd. The “ten men” (or ten people now in some communities) needed for a “Minyan” in order to recite certain prayers that require the “community” to “testify” in favor of G-d is done in this way in order to try and make up for or make amends for the Sin of the Spies; who did the very opposite by testifying against the L-rd. So, what the Gershonites would be doing with regard to the work related to transporting the elements of the “Mishkan,” was apparently G-d’s original plan but to continue only until the Jewish People would capture and settle in Canaan, the Promised Land. What transpired as an upshot of the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” (the Sin of the Spies) catapulted the mission of the “Mishkan” to a wholly different level in terms of how long it would be needed and for who would be “drafted” to serve in its upkeep and maintenance. The Torah does not address the following, but, in trying to gain the clearest possible understanding about which Jewish People was being discussed at that particular time and what the lives of that particular group of Jews were like, we want to focus for a brief moment on what might be termed the “down time” of the Gershonites. By “down time” we are referring to the times between the actual transporting of the soft parts of the Mishkan. Once the orders to strike the camp were issued, work for the Gershonites would begin and would not stop until the entire population had moved to a new location and the Mishkan was reassembled. After that; i.e. after the Mishkan was reassembled and functioning, we wonder what the Gershonites did while the Camp was in place. There was no packing or unpacking to do. The Mishkan was reassembled and functioning, which would not require any assistance or attention from the Gershonites until it had to be moved again. So, what did the Gershonites do all day while the Camp was in place? Perhaps there were certain devices or pieces of equipment that were used to protect, move, repair and otherwise tend to the elements that made up the Mishkan that needed to be fashioned, adjusted or repaired, so that when the next move was ordered that all would be ready to go. But, was that work enough to have kept the Gershonites busy in between moves? It is hard to imagine, but perhaps the weather and fragility of some of the elements of the Mishkan was such that even when the Mishkan was fully operational, there may have been certain maintenance functions that needed to be performed to keep the Mishkan up to the standards required for its very important functions. In any case, we can not imagine that people just sat around doing nothing while the Jewish People were en route to the Land of Canaan and surely not later, after the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” when the Jewish People would “wander through the desert while waiting for the generation of the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” the Jews who had actually been slaves in Egypt; who had known the feel of the lash of a whip on their backs and who, apparently, lacked the level of faith in the L-rd to have followed Him but, rather cried out against the L-rd, and, by doing so, earned themselves a decree of death by natural causes while wandering in the desert, to finally die. They must have done something in return for being allowed to stay alive when they very well may have been killed like so many of their generation had before them. Food came from “Manna,” which was gleaned daily with two portions gleaned on the eve of the Sabbath. So, there was no farming to be done. Perhaps there was some kind of cooking to do that involved the Manna. In any case, our thoughts wonder around as the Gershonites did wondering how they did fill their day when they were not moving the Mishkan to the next encampment. One thing we do know about the extensiveness of the work that the Gersonites did do, was that there needed a certain degree of organization, which came in the form of Ifhamar who was the younger son of Aaron the High Priest (Numbers Chapter 4 Verse 28). Ithamar was apparently the coordinator, superintendent or “man in charge” of what the Gershonites did with regard to the Mishkan. Ithamar and his older brother Eleazar served as priests after the deaths of their two eldest brothers, Nadab and Abihu, who had been punished by the L-rd for having performed an unauthorized sacrificial offering. Ithamar and Eleazar are regarded as direct male ancestors of all Kohanim (the priestly class). Years ago, that last sentence would have needed no explanation. But, the word “Kohaniem,” which is the plural of “Kohain,” in some segments of the Jewish Community today has been all but driven into obscurity along with other similar terms, and with what were universally considered important vestiges of Jewish heritage and that are now preserved and maintained mainly in the traditional (read: Orthodox) segments of the Jewish Community. At the risk of boring those who know or still remember what a Kohain, a Bas Kohain, a Levy, a Bas Levy and a Yisroael is and what Duchaning means; the following is a brief explanation: After the fall of the Second Temple, life in the Jewish Community took on new customs since there would be no Holy Temple to serve as the center of Jewish life. Eventually, there developed the idea of synagogues where Jews in each community or neighborhood could gather to worship G-d through prayers to which they would first listen as they were recited or chanted by those who were talented enough to compose or to even offer such devotional words extemporaneously. In time, certain prayers became accepted and shared from community to community so that Jews could join communal prayer meetings almost anywhere and be familiar with what was being said and done. Over time, the tribes of the Jewish Community blended one with the other to where there was no discernable identity of one tribe from the others. Those who had been in direct service of the Holy Temple were more clearly identifiable even when the Holy Temple was no longer part of the equation. In order to maintain a certain connection to the days of the Holy Temple, certain customs were established to “honor” the direct descendants of the two families that made the Holy Temple what it had been. The Priests, who were the direct descendents of Aaron, who was the brother of Moses; were the ones who offered the various animal sacrifices and evaluated the physical conditions of members of the general community with respect to their eligibility to stay in the general community or to be relegated to stay outside of the community for fear of spreading whatever ailments they might have had. The Priests or Kohaniem owned no land and had no other means of support other than the contributions to the Holy Temple by members of the general Jewish community. In support of the work done by the Priests, the Kohaniem, were the Lavieem or Levies, who made sure everything that needed to be done to enable the Kohaniem to perform their functions was in place and in just the right way and at just the right time every day. The tasks of the Levies were seemingly endless and of every kind and type involving music, material control, maintenance, the culinary arts of the day and any number of functions. Without the Holy Temple, the position and functions of the descendents of the Kohaniem, the Priests, the Levites, the support echelon in the Holy Temple, became strictly ceremonial and commemorative of those bygone days; and perhaps, a look forward to when the Third Temple will be built. We pray that it may be so and in our time. In perhaps the simplest ways, when three or more men were dining together, which would call for them to say grace after meals together, if one of them was a Kohain, a direct descendent of the sons of Aaron, he would be asked to lead the “Benching,” i.e. the “blessings” if the Kohain deferred the honor to someone else who was not a Kohain, the leader of the Grace after Meals would say something like, “with the permission of the Kohain …” and then recite the blessings and invite the others to join in. In a much more public way, on days when the Torah was to be read before the congregation, which in our time is on the Sabbath, on certain holidays and on Monday and on Thursday mornings, the first person (man above the age of Bar Mitzvah) called to the Torah would be a Kohain. The second person would be a Levy. But, if there was no Levy present, the Kohain would stand in for the Levy. If there was no Kohain present and a Levy was present, the Levy would be called up in place of the Kohain with a phrase such as “in the place of a Kohain.” Clearly, the courtesies paid are not to the Kohaniem and Levies themselves as individuals, but, rather, as representatives of the Kohaniem and Levies of the days of the Holy Temples who had dedicated their lives to the service of the Jewish People. The original plan for the source of Priests for service in the Holy Temple was not from one particular family but, rather, it was to be from the entirety of the greater Jewish community. Yes. The first born sons of every family were to be “dedicated” to the service of the Jewish People by becoming Kohainiem. Eventually, that original plan got supplanted by the idea that the sons of Aaron would be dedicated to the work of the Holy Temple. As a remembrance of this “change of plan,” when a first born son is circumcised, which welcomes him into the Jewish religion, if he is not born into a Kohain’s family, there is a symbolic exchange of money by the parents of the new baby who give a coin or coins to a Kohain as a symbolic way of redeeming their son from the “obligation” to serve the Jewish Community as a “priest” and, instead, to remain a regular person with no such obligation. It is, of course, totally symbolic, but, was always quite special for all involved and was a way of linking the rich and really, the amazing history of the Jewish People with the Jews of today. The other, and perhaps the most wonderful ceremonial application employing Kohaniem and Leviem in modern day Jewish ritual observance is the “Bierchas Kohanies (the Priestly Blessing or the Priestly Benediction), which is referred to in rabbinic literature as Nesiat Kapiem” the “Raising of the Hands” or in the Yiddish as “Duchaning,” which is from the Hebrew word “Duchan,” which means “platform.” “Duchaning” starts before it starts. Sounds crazy but, it is very special. Here is what happens and we can talk about the “whys” later. The Kohaniem and the Leviem in the congregation leave the main sanctuary and adjourn to a place in another room or in the hallway where there is a water source or the needed water filled pitchers and basins for catching the used water has been set up. The Kohaniem remove their shoes, which means they need to wash their hands since unwashed hands after touching ones shoes would be antithetical to the high level of sanctity that the ritual in which they are about to participate will demand. (Really, returning to the sanctuary to do anything, even to just participate as a congregant, would still require the “elevating” of ones hands after doing something of a defiling nature, before returning to participate in ritual and spiritual activities. The prayer we recite before the “cleaning” or “washing” of the hands is “al nitelas yadiem,” which is translated most accurately as “concerning the lifting up or elevating of the hands.” Clean is one thing. But, the purpose of the cleaning counts as well. Using the hands in prayer would require them to be not just clean but ritually uplifted to the task at … sorry, hand). The Leviem use pitchers of fresh water to pour water over the hands of the Kohaniem. The spent water that drains off of the hands of the Kohaniem drips into a basin placed beneath the hands of the Kohanies to keep the water from spilling onto the floor. The Kohaniem dry their hands on a towel or on paper toweling and then return to the sanctuary. They walk to the front of the congregation and, depending on the architectural structure of the building, which would mount the platform where they would stand facing the “Aron Kodesh” (the Holy Ark where the Torah Scrolls are kept). That “platform” element is where the name for the ceremony, “Duchan,” and “Duchaning” is derived. At the appropriate point in the service, the Cantor calls or sings out to the Kohaniem, which is their “cue” to place their Talaciem (prayer shawls) over their heads in such a way as to cover their faces completely and such that when they will later stretch out their arms and hold them in front and slightly over their heads, their faces will still not be seen by congregants who might look at them. (Typically, the “tallis,” or “prayer shawl” used by Kohaniem who participate in the “Duchaning” ceremony will be significantly larger than ones used by most anyone else specifically with the requirements of the Duchaning service in mind). The Kohaniem then chant the blessing that is recited just prior to performing this ritual, which is the chanting of the world famous tripartite blessing that is actually included later in our Sedrah at Numbers Chapter 6 Verses 23 through 27 and which was dictated by the L-rd to Moses to direct his brother Aaron to recite to the Jewish People.. After reciting the blessing, the Kohaniem turn to face the congregation even though their Talaisem, prayer shawls, will have been already completely repositioned to cover their faces entirely from view. As the Kohaniem turn, they raise their hands and arms in front of them and extend their fingers on both hands in the sign of the Kohain, which is the pinky finger and the ring finger held together. Then, a separation between the ring finger and the middle finger, and, then, the middle finger and the index finger held together with the thumb extended out away from the other fingers and the palm forming an unmistakable and memorable symbol that, during the recitation of the Priestly Blessing itself, is never seen by anyone. Both hands and arms are raised and configured in this way. Nothing is taken for granted. The Kohaniem are, of course, unable to read the blessings they are about to recite so, the Cantor or the Rabbi calls out one word of each blessing at a time and he does so “belachash” (in a whisper) so that only the Kohaniem can hear the words. The Kohaniem chant each word slowly out loud and, between the words, the Kohaniem chant an ancient melody until the Rabbi or Cantor calls out the next word of the benediction, and so on to the end of the entire three part blessing. The congregation, at the end of each verse, says, “Kain Yehee Ratzon.” This means “so, may it be His will.” The congregation does not say, “Awmain” (amen). If you are thinking, “No big deal” please think again, because it is actually a very big deal. Each phrase has its own meaning and, particularly in the instance when the people are experiencing the “Priestly Blessing” being spoken by the Kohaniem, how and what the congregational response indicates whether those responding have any idea as to what is being recited for by the Kohaniem for the benefit of the congregation or not. “Awmain” (Amen) means, “I agree.” That is a fine answer or response when responding to someone who has recited a blessing over food, as an example, “Blessed art thou oh L-rd our G-d who has created the fruit of the vine.” And we can respond, “I agree.” Or, “Awmain,” (Amen), and, by doing so, be a part of the making of the blessing ourselves and, thereby, are free to eat or drink the food for or over which the blessing was made. The “Priestly Blessing” is a completely different affair. We will dig into the “Priestly Blessing” as we get to those specific verses in our Sedrah. For now, let us just say that the recitation of these verses where the Torah tells us of what G-d told Moses to tell Aaron to Bless the Jewish People is not something with which one would simply “agree,” by saying “Awmain,” but, rather, it is, something that we, any of us, would want to be, thus, the response, “so may it be His (G-d’s) will,” is the appropriate response. Are we making more about this than we need to be? ”We might think so if we had not personally experienced “Duchening” and, therefore, we feel the need to point this difference out. Yes. In a synagogue that holds itself out to be “Conservative” and which sublimates almost everything that has to do with “Kohaniem,” “Leviem,” and Yisroael” lineages save for the way a person’s Hebrew name is structured, the “Priestly Blessing” or “Duchaning” has been “shelved” almost completely; i.e. that is as we have just described it. But, very recently, with no explanation or reasons given, the rabbinical leadership has introduced the recitation of the tripartite blessing into the conclusion of the Friday evening service. Traditionally, the “Priestly Benediction” ritual is done in a very formal and, admittedly, a very dramatic way. In this current instance, the verses are recited in a completely unceremonious way with congregants responding, if they responded at all, with “Awmain,” as if they were about to eat a piece of fruit and with absolutely no appreciation of what those three statements dictated by the L-rd to Moses to relate to Aaron means or of their importance to us. To someone who has known the powerful feeling of “Duchaning” from the point of view of the Kohaniem and having spoken with congregants who have participated in the ritual as Levieim or Yesraailiem and to have listened to their reactions, the “throw away” manner in which these powerful and important phrases dictated by the L-rd for recitation by the Kohaniem (the Priests) to the Jewish People are made is absolutely revolting. Is there a president somewhere in our history for doing this i.e. for minimizing the “Priestly Benediction” as is being done? Perhaps there have been other rabbinical leaders who did something like this; i.e. who reduced what are the “Priestly Blessings” to a shadow of what that ceremony is when done the way it had apparently been intended to be done. Would that make it right? In our humble opinion, it would not. Why do so many of the spiritual leaders of the day choose to do this; to minimize and even trivialize what are such amazingly meaningful parts of our Jewish Heritage and religious practice? We can only guess that they are focusing on what might be referred to as equality issues. Women are equal to men now. Women are counted for a “minyan” (a religious quorum) now. Who needs the “Kohaniem,” “Leviem” and “Yesrael” distinctions any more? Just throw away that entire heritage in favor of having next to no heritage. By continuing the honoring of our heritage with the honoring of a particular man who might be a Kohain is the, perhaps, the seed that grew into this drift, or really a movement, away from our religion’s heritage and towards a diluted, weakened and less glorious version of Judaism that will, in time, fall of its own weight into oblivion, leaving the segments of the Jewish Community that work diligently to preserve the heritage of the Jewish People to go forward as that People. Those members of the Jewish People who have never experienced such ceremonies as “Duchaning,” --- if indeed there is anything else that resembles the drama and power of the “Duchaning” ceremony -– for them, they simply do not know what they are missing. In Numbers, Chapter 4 Verse 29, the Torah moves from the Gershonites and their responsibilities to the sons (children) of Merari and outlines, in a similar way, their responsibilities regarding the Mishkan. Where the Gersonites were more focused on what might be called the soft components, such as the coverings, the tent material and similar accoutrements, the Children of Merai were to focus on the infrastructure and connective elements. And, in Verse 32, we learn that it seams that each of the many such hard elements was to be assigned to particular members of the family, which could tell us just how important those elements were regarded. The overall responsibility for what the Childern of Merari did was supervised also by Ithamar the son of Aaron the Priest. The Torah moves next to the census of the families of the sons of Aaron, the Kohaniem, who were the ones who were responsible for the entire life, rituals and ongoing of the Mishkan. Again, those men between the ages of thirty years of age and fifty years of age were to be counted. And, at this juncture, the Torah seems to draw the line under all this counting and reports to us the numbers in each of the families, which work out as follows: The Kohaniem totaled two thousand seven hundred and fifty (Numbers Chapter 4 Verse 36). The Sons of Gershon totaled two thousand six hundred and thirty. (Numbers Chapter 4 Verse 40). The Sons of Merari totaled three thousand two hundred. (Numbers Chapter 4 Verse 44). The Torah explains or reminds us at each numerical report that these numbers reflect those men in each family who were between thirty and fifty years of age. Then, as if to draw a line under the figures thus far presented, the Torah does the math for us and adds up the census counts of all those who were in and with or around the Mishkan, i.e. the Gershonites, the Kohaniem and the Meraris for us to ponder; eight thousand five hundred and eighty. (Numbers Chapter 4 Verse 48). As the Torah concludes its reporting on the results of the counting of all those who work in and with the Mishakan, it reminds us that this counting or tabulating of how many men did what they did in the Mishkan because it was so ordered to be done by the L-rd who commanded Moses to do so. With all due respects, we have been told this at every juncture during the reporting of these numbers of people – men – who work in and with the Mishkan. Why does the Torah feel obligated to repeat it once more as the counting is concluded? Perhaps the Torah shares with us again that the L-rd commanded Moses to take a tally of those who worked in, with and for the Mishkan to impress upon us the importance of the tasks and the overall mission of the individuals who will be doing the work and by the entire work force and of the staggering complexity of the work that they actually have to do with such a limited number of people to accomplish all that needs to be done to maintain and run the Mishkan, which was, after all, where the L-rd Himself would reside while among His Chosen People. Do we dare look beyond this fairly obvious reason for the Torah’s great focus on the work of the Mishakan and that all that is done relating to it is done at the direction and commandment of the L-rd? Without much of a stretch, we can think of our situation today and see if we can apply anything related to the L-rd’s commandment regarding the census of those who worked in and for the Mishkan and those people today who serve the Jewish community in, around and for our various religious gathering places, such as our synagogues, our temples and institutions of Jewish learning and even at ad hoc locations when a minyan (religious quorum of ten Jewish men or today in some communities, ten Jewish people). Of course, since the fall of the Second Temple in the year 70 CE (Common Era), the Jewish People have been using synagogues and similar such institutions as quasi-centers of Jewish religious life for the most part relying on symbolic references to the L-rd and realizing that where He (the L-rd) was in residence in the Mishkan and in both Holy Temples, that is not the case in our current day houses of worship. What we can learn is that, to a greater or lesser extent, what ended up getting the Jewish People exiled from the Holy Land and the fall of the Second Temple is what is keeping the Jewish People of the day from being redeemed. We can pray and ask for redemption all we like. But, until the Jewish People are actually deserving of redemption by the L-rd, redemption will not take place. So, “what to do” is the follow up question. What may be the answer is to treat the current day houses of worship with respect and attention to detail that was the standard in the days of the Mishkan and of each of the Holy Temples. And, remember please, that the Mishkan was used as it was; i.e. the portable residence of the L-rd amongst the Jewish People, who were, at first, making their way directly to the Holy Land, and, then, after the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” (the Sin of the Spies) as they “wandered” through the desert waiting for the generation of the “Chait Ha Miragleem,” to live out the remainder of their days before the L-rd would, finally, deliver on His promise to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob by delivering their descendants to the Promised Land. What that might lead us or our spiritual leadership to do, is to get back on course to what the L-rd was orchestrating in His commandments to Moses regarding the stewardship of the Mishkan; who was doing what, when and how. That might well bring us back to reinvigorating the symbolic uses of the Kohaniem and the Levites in hopes of energizing the Jewish Community (the Jewish People) to acting the part of wanting the Holy Temple rebuilt in our time and not simply saying the words to that effect. Talk is cheap. Leaning away from the ways of the L-rd are what got us where we are. Continuing to lean away will surely not be the way to bring about redemption. Actions speak louder than words may be the answer to our question. The Jewish People of our day needs to walk the walk and not just talk the talk. But, the responcibility really lies not with the spiritual leadership. That is why the L-rd called for and commanded that a census be taken; to count everyone who would be doing what needed to be done. So, today, each and every one of us who would be counted in such a census needs to roll up our sleeves and get to work to get us back in the “holiness game” so we will be ready to be redeemed when redemption finally comes. In Numbers Chapter 5, the Torah continues its efforts to make things just right for welcoming the L-rd into the midst of the encampment with its focus now on what might remind us of the phrase “cleanliness is next to godliness.” In Numbers Chapter 5 Verses 1 and 2, we learn of G-d’s having spoken to Moses and telling Moses to “command” the Children of Israel … that is right. There is a different approach. Before, in Numbers Chapter 4, it was the L-rd making the commandment to Moses and, through Moses, to the Jewish People. Here, in Chapter 5, G-d is telling Moses to do the commanding. One might say that it comes out to the same end. But, the Torah does nothing frivolously or without purpose. In this instance, it does not explain the difference nor the meaning behind commanding directly and telling Moses to do the commanding. But, perhaps the reason is indicated at the end of Numbers Chapter 5 Verse 3 where the Torah details who is to be expelled from out of the encampment; i.e. both male and female, and an explanation as to why; really two reasons are given. One, that they (those who are defiled in certain ways) so as not to defile the others in the camp; and, two, that they not defile the camp in the midst of where the L-rd dwells.. Again, it sounds like the same or just one reason, but it is a compound one. The encampment is not to be defiled and, two, where the L-rd dwells is not to be defiled. We could ask why the L-rd is concerned about defilement if, in essence, He (the L-rd) created the entire world; that which is considered defiled included. In other words, the L-rd will not and could not be risking being defiled by having that which is defiled in His (the L-rd’s) presence. So, why is there this concern in this way? Something that one of our teachers at Yeshiva College in the 1960s shared with us about “holiness” may help explain the L-rd’s objective here. Rabbi Steven (Shlomo) Riskin (May 28, 1940 to the present) was explaining why a woman who is going through her menses (her period) is considered “unclean” until afterwards and when she then goes to a mikvah (a ritual or spiritual bath). The rabbi explained that what is in focus in this subject has nothing to do with being dirty or soiled or even impure, but, rather to do with the concept of “potential” as compared to what the rabbi termed “unfulfilled potential.” The woman’s unfertilized egg stands in contradistinction to the living person it could or might have become had it been fertilized and developed into a baby. Once passed out of the woman’s body, that “egg” and all of that woman’s body and what it needs to go through to reset itself to where she is able to conceive a child again, makes her both actually and symbolically representative of “unfulfilled potential.” Rabbi Riskin likened that state of being to when one comes in contact with a dead (human) body. A person who is dead is the essence of unfulfilled potential. While alive, we all have potential to do things. At death, a person’s potential is gone. Judaism draws the distinction between the two states of being and asks us to take steps to do things that distinguish one state from the other. So, if we come in contact with a dead (human) body, we are to consider ourselves in need of ritually purifying ourselves, which would involve emersion in a “mikvah” (ritual bath). With Rabbi Riskin’s clarification of ritual cleanliness and un-cleanliness in mind; i.e. potential vs unfulfilled potential, we can, hopefully, see what the L-rd was asking of Moses when in Numbers Chapter 5 Verses 1 to 3 He (the L-rd) directed Moses to command the Children of Israel to put out of the camp every leper, everyone who has an issue and whoever is unclean by the dead; i.e. having come in contact with a dead (human) body. The idea or the objective seems to be to do what we can to distinguish “holiness” from the “opposite of holiness;” i.e. from where potential is still possible from that which embodies or is representative of the complete lack of potential; i.e. unfulfilled potential. And, it is not so much for the L-rd, even if it says the L-rd will be dwelling in their midst. It is for us, even for us today, with no Mishkan or Holy Temple extant, to do what we are able to do to live a life of “holiness;” i.e. to use our potential to do good deeds; to create as we are able and to help others in the way the L-rd helps us, and to do so while distinguishing against that which represents, or is the antithesis of life’s potential. The Torah continues in Numbers Chapter 5 Verses 5 to 10 to dial in on aspects of life that would bring people in direct contact with the Mishkan. Individuals can do what might be said is leaning away from “holiness” and, therefore, need ways to remedy their mind set and re-acclimate their ways to be worthy, again, of a life of decorum. So, when someone acts in such a way as to transgress basic interpersonal and communal norms, he or she would be required to come to grips with what they had done, which would involve two levels of repentance. One, would be to acknowledge to themselves and publicly that they had done wrong and that they were, indeed, sorry for having done so with a commitment to themselves that they would endeavor to be more respectful of such societal ways of working going forward and, two, to couple that with a physicalization their commitment in the form of an offering; which is the bringing of a sacrifice, which is basically a charitable contribution in the form of an animal, which would be slaughtered by the Kohaniem on behalf of the one looking to express atonement and retained by the Kohanin for consumption by the Kohain and the family of the Kohain. The Torah, in Numbers Chapter 5 Verses 11 through 31, broadens further the responsibilities of the Kohaniem as part of their services to the community in the Mishkan by detailing what was to be done in the event that a husband believes that his wife has committed adultery but has no witnesses or any proof that would substantiate his belief. Today, we would be wanting to see some kind of evidence or convincing testimony by people who would swear that they had seen the woman in question keeping company in such a way that a physical relationship between that woman and a man who is not her husband could have taken place. It is the exact same testimony to which the two witnesses at a Jewish wedding attesting that they saw the bride and the bride groom enter a private room, close the door and emerge later having had sufficient time to have consummated their marriage. But, in the situation in Numbers Chapter 5, the husband does not appear to need such substantiation of his concern or belief about his wife’s “possible” adulterous activity. Here, the Torah describes in great detail what is referred to as a trial by ordeal involving the woman being made to bring various sacrifices to the Mishkan and where she would be made to wear her hair unbound, which was apparently symbolic of a woman with loose virtues, and made to drink a concoction of holy water and dust from the floor of the Mishkan after being made to swear that she had not had sexual relations with anyone other than her husband. If she were telling the truth, there would be no physical reaction. However, if she were adversely affected by having ingested the holy water and dust from the Mishkan floor, it would be taken to mean she had been swearing falsely and had indeed been unfaithful as her husband had suspected. Apparently, the husband’s accusations or feelings “proven” wrong was not something for which he would be held responsible. But, if the wife were “proven” guilty she would be made to bear her iniquity. What the Torah means by “bear her iniquity” is not defined at this juncture. There are those who hold that these “practices” were more for keeping people from even daring to stray in such ways for fear of being found out even if they had been able to be with each other without having been noticed by others to where they could have been brought to task. When reading this, it is our hope that the procedures described were able to be sufficient deterrent to those who might consider straying in this way from their marriage and that it never had to be actively used by the Kohanim with real people. Numbers Chapter 6 talks about the Laws of the Nazirite, which means “consecrated” or “separated.” It is important to note that one who decides to be a Nazeer does so for their own individual reasons that come from deep within and which motivate them to dedicate themselves to live a purposely austere life for a specific period of time, usually for thirty days at a time, but which could be for significantly longer time periods as well. We learn that a Nazerite does three things to help himself or herself dedicate his life or her life during that period of time to be more focused on G-d. The areas of focus for a Nazerite are as follows: